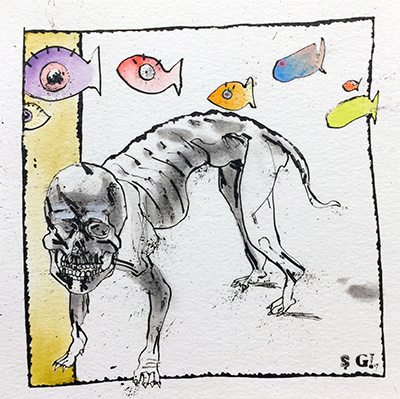

Illustrated by Scott Gandell

We were the last house on Taitano Street, where lost things found their rest. The road was hugged by houses on one side and boonies on the other, ending on a rocky platform of shrubs that dropped into a cliff. Stray dogs would often emerge from the boonies and meet in our driveway, pawing and scraping at the screen door until we answered.

“Give them the scraps,” Ba said.

“Even the bones?” we asked.

“Even the bones.”

We didn’t know we weren’t supposed to. We just threw the scraps out the door because Ba said so, and we always did what Ba said. We listened to the crunch, crunch, crack. They’d return the next day and the next, until they decided they could stay.

“Hey, piece of advice,” said the man who lived next door but never bothered to find out our names. “Keep your dogs in your yard or I’ll shoot them.” Everyone’s family on the island unless they’re not. Chamorro blood runs deep and pulses through veins of dirt that run the island; the blood of Vietnam refugees is a different blood, an unspoken and nonexistent one.

——————

On days like today, when the house is quiet and the power is out, Rhosabelle and I would spend afternoons on the street throwing rocks into the boonies. We would stand at the edge of the trees, afraid to go any deeper, and watch them disappear into the shadows, never really knowing where they found ground. Over the years, the older dogs would return to those same shadows they once emerged from, and we would never see them again. One of the only dogs left, Pepper, ran between the two of us to chase the rock I had just let fly, but even he didn’t dare run in too deep.

I watched Rhosabelle take her turn and stretch her arm back before swinging it forward. She looked everything like me but was nothing like me. Our necks were long and our noses short, our hair strong and our eyes weak. But I always ate up the island stories since we were little, like the one about a beautiful daughter from a long time ago who was buried with beautiful flowers, and then a magical twenty-foot-tall plant shot up to bear coconuts for the Chamorro people. Meanwhile, Rhosabelle would break the flow with her questions. Why was it magical? How long did it take? How does a girl grow coconuts?

Lately, though, she’d been the one who was somewhere in a land far, far away.

“You fold wontons the fastest. Who’s going to fill in for you?” I asked.

It’s not like I didn’t understand why she was leaving. Of course I did. Uncle Joe told us that there were only two times people could get off this island: in their late teens or in death. He chuckled to let us know it was a joke, but we didn’t take it as one.

“I’m sure the restaurant will be fine,” she said. She picked up a bigger rock, pivoted to face the boonies, and chucked far.

I thought about her writing papers in her dorm while I wrote tickets at Ba’s restaurant.

I rolled another rock around in my hand, feeling its small peaks and valleys carve its own invisible lines on the same palm that clung onto Rhosabelle’s when we were born.

“You could have gone too, you know,” she said when she heard my silence.

“Ba doesn’t like putting money where there’s no worth, you know.”

She took my silence and made it hers. It’s what she always did with everything I tried first. We stood there, alternating throwing rocks into nowhere.

I gave in.

“Do you remember the story about Sirena?” I asked.

“What about it?”

The legend of Sirena was Rhosabelle’s favorite, but it was mine first. You would know she loved it because she would ask no questions every time it was told. She accepted that Sirena’s lower half was turned into a fish because she used to sneak away from chores for swims. She let Sirena’s mother curse her daughter and knew Sirena would never come back after diving into the Pacific. She told and retold how Sirena was seen by seafarers everywhere and could only be caught with a net of human hair.

“Can you just promise you’ll come back?”

When we were seven, I said I wanted to swim across the ocean and find Sirena. When we were eight, Rhosabelle actually tried to make a boat out of sticks and rope. When she thought it was ready, she made a scene out of saying goodbye to everyone. We watched as she sat on her makeshift boat and slowly sank, just a few feet from the shore. Ba laughed it off, but I knew it would happen one day. That night, I pulled the ends of my hair to my eyes and wondered how many haircuts it would take to save enough hair. Just in case.

“I’ll come back if you can throw farther than me,” she teased. It was a game we had played long before.

Rhosabelle picked up a big rock and flung it down the road, parallel to the boonies.

I kicked my shoes into the dirt until I found one I wanted. The rock flew past one house, two houses. It found the ground in a burst of energy, but before we could react, two of the neighbor’s sixty-pound mutts jumped the fence and rushed at us.

Without even looking at each other, we both took off in a bolt. We ran the fastest we had ever run, the dogs’ barks pushing our feet. We ran along the boonies—the boonies where the Taotaomona spirits slept and would pinch you until you bled if you didn’t visit with respect—the boonies Ama walked into with a dead, five-foot-long brown tree snake because it had coiled around our kitchen pot, the boonies that watched us grow and told us stories, the boonies, which would later be cleared, long after Rhosabelle left the island, to build bigger, more beautiful houses for new military families.

We ran along the boonies and toward the busy main road. We ran along the boonies, away from a home that had fit six, ten, sometimes fifteen relatives in three rooms. As we reached the red mailbox Ba had always tapped for luck, I watched her surge forward and knew I wouldn’t catch up.

I watched her run along the boonies, jumping across ever-deepening potholes, until I could hear the barking fade, until I knew she was safe and could find a place to rest.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.