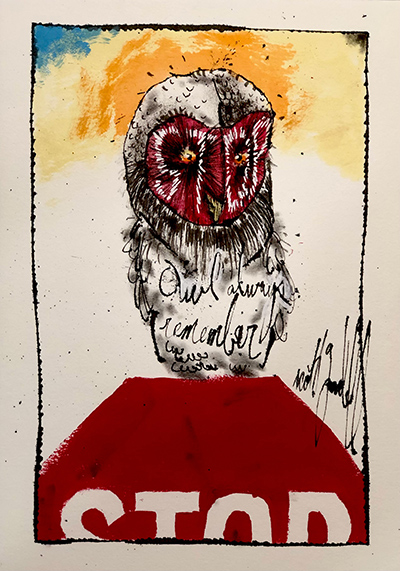

Illustrated by Scott Gandell

Every now and then I get a call from the BBC.

The first one was from Night Flight, a program that, I guess, covers the world. They wanted to know my reaction to the Rodney King verdict and would I write a piece for them and they’d even pay me. It was a decent amount for a short piece that they never ran but it was good to write it and it later evolved into the Geography of Rage, a collection of essays from those of us who survived the Rodney King Rebellion.

I was in my second year in UCI’s MFA program where good people and some asses agonized over the potential success of their fellow workshop writers when the Rodney King Rebellion exploded and I had something real to worry about. I took to wearing my Malcom X baseball cap to give my light skin ass some protection from flying bricks or whatever else. I didn’t really take my personal safety as that big an issue, but Gina did suggest that I stay home the night when it officially became a region wide riot. I needed to walk the dog and I went out into the night from our black working-class neighborhood that abutted the freeway. The city of Pasadena, like many cities, was brilliant at blowing up neighborhoods of color by building freeways or parking lots, just about anything to cut right at the economic heart of the black or brown community or Asian just to show us that they could do some vile racist city planning. My usual walk was above the Rose Bowl with Buck, my beloved genius husky. Sometimes we would have a barn owl follow us and alight onto a stop sign where we would sit on a bench and watch it. This time though I heard squealing tires down at the Rose Bowl. I stood on the edge of the hillside and I could see cars caravanning around the 3.5 mile loop and then I heard rapid gunfire and then the cars peeled off in opposite directions. Then it occurred to me that they might want to drive through this affluent neighborhood and shoot it up and maybe even my working class/middle class ass might look affluent enough to shoot at. I disappeared into a hedge and pulled Buck low, but no cars came in our direction.

As I walked back to my neighborhood and when I got to Lincoln, I saw a black woman rolling a large engine jack into position to lower the engine out. I was surprised not because she was a woman, but that it was one person job. When my dad or brother did that kind of thing, they had help. Obviously, this woman didn’t need it.

I said before I knew I would say it, “There some fools shooting up the Rose Bowl!”

She paused from her engine work and looked at me shaking her head in disgust.

“I told them fools not to be doing that. Ain’t nothing good gonna come out of that mess.”

“Oh,” I said, wanting very much to be on my way home and she could sense it.

“You better get home before it get crazier.”

“Yeah,” I said.

“God bless you,” she said.

I said thanks and started hurrying away, but before I take more than a few steps she said, STOP! I stopped.

“You didn’t say God Bless you to me,” she said with a playful seriousness.

My mouth fell open and after an awkward moment I said, “God Bless you!”

She smiled and waved.

“Get home and be safe.”

I’m not religious, but for that moment I was a devout Christian, blessed by a black woman who had more heart than I ever had in my life.

I hurried home glancing back at her. Though I lived on Lincoln for another few years, I never saw her again.

Interesting memory