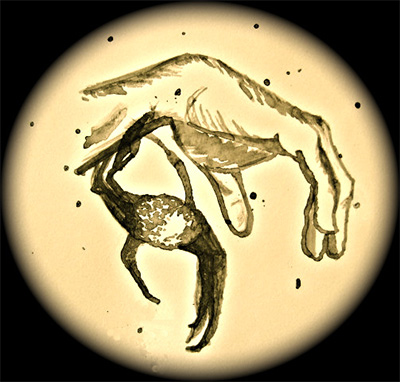

Illustrated by Allison Strauss

Hey Cooter, look what got ahold of me! Treufel hollered as the boat pulled in. I grabbed the lank of yellow rope where Janie threw it and tied them off. Some kind of crab it looked like, attached to his arm – squat, orangy-brown, with nubs around the pale edges of the shell like the ones that hurt your palm when you crack a leg for the meat. I asked him what is it? but he just shook it in my face, making boogety noises. Treufel was your basic idiot – untucked overlarge shirt in a picnic-tablecloth pattern with the pocket torn off, hair out in every direction, voracious lop-toothed grin. He looked like a cartoonist’s idea of ruffian. We were stuck with him for two more days.

On weekends our family existed in a paint-by-numbers world of blue lake and sky, orange lifejackets and the red and white of fishing floats. At the cottage it was popcorn for dinner, a battery-powered radio that picked up one AM station, and the complex deterioration of shoes and shirts Mom wouldn’t let us wear at home. Dad hadn’t come this trip, he had accounting to do. If he’d come, he said, he’d just fish, his taxes would go to hell and we’d all end up in jail. It was Mom and me, Janie and Treufel, plus our little brother Beck and Treufel’s sister Anastasia, who had her brother’s raggedy-doll looks and bad teeth but none of his aimless energy. Treufel was Janie’s boyfriend and in our family if anyone wanted to bring someone else on the picnic or car trip, the attitude our dad encouraged was, the more the merrier. The more the uglier, he’d joke with me or Beck when we asked to come along on a run to the marina to fetch bait or supplies.

The body of the thing was curved, the size of an adult’s hand, hanging on Treufel’s wrist by some kind of grippers at its front end. I first thought it was plastic or else why would he cruise into shore with this jokey thing on his arm, whipping it around and laughing. But when he knock-knocked its shell with the hook remover a couple of multi-jointed extremities unfolded and wheeled slowly about like the legs of a dreaming cat. Cycling in the air like it didn’t have a care or a hurry in the world because it had ahold of Treufel.

They’d left after breakfast. I stayed behind, read Popular Mechanics and worked on my arm muscles. If you’re fishing and want to come back early but the others don’t, that’s your tough luck. They could be out six hours, ten, fourteen – fishermen lose track of time. I’ll cast a lure off a dock but I get hungry. I like to pace, pee, swing my arms. Also, I’m not fond of the nose-pinch waft of live bait, or the ick of a bass left under a fiberglass seat for five hours, drying out so the slippery shine it came out of the water wearing turns to sad yellow glue.

I’d checked with the binoculars around noon and saw them heading in. Mom kept the big Bushnells to watch for Dad, see if he was moving out there beside the island. If he changed places a lot, rowed along parallel to the rippling tips of the pines, that meant nothing was biting and he wouldn’t stay out long. Whereas sometimes he’d bob in the same spot eight hours and still come home with nothing. He didn’t take the radio or a sandwich, all he did was fish. Mom would sit on the deck and smoke with the binoculars on her lap. I don’t know which of them was more patient.

Treufel jumped out and sprawled flat on the dock so the crab thing, except for being locked on his bony arm, was standing free on the grey planks, or could have if it wanted. I helped build that dock when I was ten – the nails with heads canted like ingrown toenails were mine. “Look,” he said. “Lookit that. I give him a chance to walk away and he doesn’t! He’s just hanging on like he loves me. Cooter, what do you think of that?” Beck, who was twelve, jumped excitedly out of the boat and said, “Cameron, it won’t let go! It’s been on there nearly an hour!” I took a closer look. Besides the waving insectile legs it had twin pincers coming out underneath I guess the head. They’d claimed a good-sized piece of the thin edge of his wrist. Pincers or not, it looked to me like Treufel could have pulled it off if he wanted. But then he wouldn’t get to whoop and holler and shake it in everyone’s face. I thought, someone must have bought it for dinner but couldn’t bring themselves to boil it, so they tossed it in the lake to fend for its mean self. I asked, “How’d it get on there?” Beck said, “He was trawling his arm through the water out by the island and bam!” Treufel hoisted it in the air, cackling, and teased one of its back legs. Anastasia stepped out of the boat, rejecting my offer of a hand. She always looked shivery-nervous as though we’d kidnapped her. I didn’t understand why she’d come.

Treufel ran hooting and yowling up to the cottage to show his prize to our mom. I thought, well, that’ll endear him. Our patchy grass had the fireworks smell of gopher bombs, incendiary tubes you lit and stuffed down their holes to drive them from your lawn over to the neighbors’. Anastasia plodded up the long green rectangle after him, shedding her life vest. I felt sorry for Treufel’s sister, freckled and compliant, with three older delinquent brothers and an outsized name she showed little sign of having the spirit to grow into. It was Dominion Day. The night before, Beck, Janie and Treufel had gone out in the boat after dark and waved lit sparklers at us, tracing shapes in the mirrored blackness, circles becoming eights where they touched the lake. Beck asked me afterwards to guess what shape he’d made. I said a drunken snake. He yipped a laugh, his blond hair bobbing, and said that’s for sure what he’d draw next time. There were real snakes at the cottage, which our mother felt she was courageous for never mentioning.

Beck unloaded the tackle, all the rods snagged on each other. He told me other than the crab they didn’t hook anything all morning; it was pretty boring. Janie whipped her long hair back over her shoulder and said if that was the case next time he didn’t have to come. “Nasty-stasia doesn’t have to come either,” he sulked. Treufel’s little sister was a year older than Beck and got off on the wrong foot the first time they met by saying she hated the television show on his t-shirt. He’d worn it since almost to falling apart. He said if Anastasia drowned at the cottage he’d be sure to bury her in it. You’re not funny, Janie told him, which was wrong, Beck often was.

The dock still held a wet blot in the shape of the thing. I tapped it with my foot. “Doesn’t it hurt him?” She shrugged. Treufel was only Janie’s second boyfriend, she was still getting the hang of it, accommodating the behavior of someone with whom she had nothing in common except they went to the same school and both disliked authority, though with Janie this was a less diffuse complaint. She didn’t like being told to clean her room and go to bed, whereas Treufel would gladly burn down the town and take pictures. Beck suggested, “Maybe we can cook that thing for dinner,” hoping we wouldn’t. I said, “If Treufel’ll let go of it. If not, we’ll have to cook him along with it.” Janie gave me one of her scowls. “He isn’t holding onto it,” she said. “It’s holding onto him.” I noticed she wasn’t chasing up after him.

Her inaugural boyfriend, Warren Kinnecky, had been the son of my Driver’s Ed instructor. Warren had a hearing deficiency and wore a device that his Baptist parents wouldn’t let him grow his hair long enough to cover. He was funny, alert, very aware of himself, my parents liked him. Janie had sat with mom and me playing Scrabble one night when Dad and Warren hadn’t come in off the lake and she asked, “Mom, you think Warrren and I’ll get married?” She was sweet that day, droopy and forlorn. She was calculating the time she’d spent alone with her first boyfriend, then adding up the long one-on-one hours our dad had logged with him out in the boat, spraying Deep Woods Off on their necks and ankles, and feeling peevish and out of sorts at the imbalance.

“Oh, I expect not,” Mom told her. “I had three boyfriends, well, they called themselves that, before your father.” I was two years older than Janie but I’d never had a girlfriend and knew not to comment.

I could see Janie adding it up: three boyfriends, then fourth boyfriend = husband. “So what am I doing it for?” she asked. “If he’s not the one? If I’ve got three more to go?” Beck and I laughed until she stared us down. “Nobody’s talking to you,” she said.

“You’re fifteen.” Mom was careful not to say only. She reached with a cupped hand and touched the bright dot of stone in Janie’s ear. Our mom was raised Doukhobor, a spacey offshoot of a hell-with-everything sect from Russia, and she didn’t have pierced ears. She’d broken with her (nutty, now long lost) parents at twenty-two, but everything modern that she went along with still seemed like a measured, faintly grudging acceptance of the freedom and options of modern kids, all the stuff she’d longed for as a girl Janie’s age, cooled by an unwillingness to cast the earliest and most vivid part of her own life completely to the wind. She caught Beck and Dad one day singing Douk, Douk, Douk, Douk-ho-bor to the tune of Duke Of Earl and told them that would be quite enough of that. Her grandparents had paraded naked through Saskatchewan in the winter of 1903 to protest compulsory education, but she didn’t want their memory, the abstract idea of a fierce heritage, impugned. Even if the grandparents had rejected everything conventional all in a lump and gone bearshit crazy out on the dry unproductive prairie.

“You’re with Warren because you like him,” she said. “Everything will fall into place, don’t you worry.” Janie looked unconsoled. Once, in an argument with our mom outside a dress shop, she’d yelled, “You’re Amish, don’t tell me about the real world!”

Now here was Janie a year later with Eric Treufel, who had a pair of older brothers my mom knew too well from working part-time in the office of the high school where they were often in for making trouble, one of them, Greg Treufel, having been arrested once for marijuana and once for joyriding in a stolen tow truck. Marlon Treufel, twenty-two, was worse – square-faced and dangerous. He’d gone west, and stories filtered back about him being an ‘accomplice’ in unsavory doings involving an older man and a girl, all three of them hunted across the border down into Washington State.

“Eric is not his brothers,” Janie told Mom when they argued about her and her boyfriend planning a cross-Canada trip once they turned seventeen. “Eric is Eric!” Janie had been a clingy mama’s girl till her mid-teens, sitting between her knees after dinner, letting Mom braid her hair as they watched television, but now all the fabled mother-daughter confrontation stuff was coming out. Dad didn’t like Eric either but could at least make a silly thunderous noise every now and then, pull a face or talk sports to keep things light. With Dad not here it fell on Mom, and she was having a hard time striking the balance of hospitality vs enforcement of household rules. Janie couldn’t help testing Mom’s opposition, pushing it like a sore tooth.

She asked when we got to the cottage why I couldn’t call Eric by his first name. I said if he could call me Cooter, which he’d picked up was Beck’s baby name for me, then I could call him Treufel. The first time he came for dinner, he challenged Beck on what kind of name that was and my dad had told him it was Viking for man who lives near a stream. Man who pisses in stream, Treufel called Beck after that, laughing his reckless head off. I tried to picture what he and Janie talked about when they were alone. I’d heard Dad one night in the kitchen discussing the necessity of talking to Janie about protection, and mom saying oh dear God forbid.

Before dinner, as the sun buried itself in the pines out on the island, Treufel sat at the folding table staring at the thing, rapping its mottled tangerine shell with the Scrabble scoring pencil. The crab hadn’t let go, who knows what it thought it’d caught hold of out there. It had tiny eyes like baby mushroom caps, on white stalks you saw if you bent and looked under its shell, which you did with the risk that Treufel would lurch it at you. My mom had examined his arm and said the red indentations looked “nasty,” which only made him cackle. She mentioned infection. We had a First Aid kit with a snakebite poison sucker bulb and razor blade that I longed to use on him. She offered to help him try and get the crab off, but he yanked his arm away.

The cottage’s square main room was dark-wood paneled, decorated with yard sale art and lightly messy in a way we weren’t allowed to be at home. Electric baseboard heaters slowly reshaped the small plastic toys Beck had dropped behind them when he was little. We kept a coat hanger behind the cheap beige drapes expressly for their removal. When we cleaned up Sunday nights, Dad would take one look around before we left and pronounce, “Good enough!” My parents bought the cottage for $8,500 in 1968 with money willed to my mother from an aunt out on the prairies who’d never forgotten her. It was on Indian land; the purchase was technically a 75-year lease. She also bought a pearl brooch and a snow blower.

Mr. Seaton called “knock knock” through the screen door. Beck must have blabbed something out by the property line. Mr. Seaton was retired from running two bowling alleys, looked like a tall Mr. Magoo, and lived at the Lake year-round, his cottage having been winterized. We had to drain the pipes in ours, flush the toilet with antifreeze and close the place up each November.

“What’ve you’ve got there, son?” Janie introduced them. I was under the tall swoopy reading lamp in the corner with a penknife, trying to carve connected links from a single strip of cherry wood the way Dad had shown me.

“It’s a devil crab from hell,” Treufel shouted, shaking it in Mr. Seaton’s face, affecting a deranged Irish accent. “It’s got its fangs in me arrm, and Oi’m gonna have to have me hand amper-tated!” He had no sense you didn’t talk to a 70-year-old stranger the same way you do to your girlfriend’s brothers.

Mr. Seaton sat on the corner of a chair, took a pair of drug store glasses from his shirt pocket and examined the crab. It tucked in its slow prospecting legs. “Looks pretty healthy,” Mr. Seaton said. Treufel did a high-pitched snickering sound and made it laugh like a drugstore puppet. Beck brought an aluminum pie pan of water from the kitchen and set it on the table. “Maybe if you put its back legs in water,” he said, “it’ll feel the water, think it’s the lake and try to escape, but it’ll be in the pan of water!” Treufel bent down and lapped from the pan like a dog. I looked at Janie. Her face was stolidly blank. Anastasia looked at the pictures in a National Geographic. Our mother made herself busy in the kitchen.

“Tell you,” Mr. Seaton said, “I’ve been up here twenty years and I’ve never seen anything like that. You might want to take it to Elizabeth Fournier around the curve; she used to teach biology.” I could have told him that was the last thing Treufel would want, to have the dangerous wild beast eating his arm downgraded to a comprehensible marine anomaly. He pried one of the thing’s back legs out from under the shell and made it bark like a dog in Beck’s face. Beck gamely stood his ground, smiling with squinted eyes as though this was great fun. Janie didn’t say anything. Mr. Seaton said well, he’d probably seen all he could, and he’d let himself out. My mom latched the door. Bugs were already harassing the yellow porch light.

Janie asked, “You want to play Scrabble, or Mouse Trap?” Treufel barked the crab at her. “You can’t go to bed tonight with that thing on your arm,” she said, one hand on her hip. For all her attempted teenaged wildness, like hooking Eric in the first place, she had our mother’s respect for order. Treufel lifted the crab to his face and mimed snoring on it like a pillow. I silently wished the thing would grab his nose.

“Okay, Scrabble, then,” she announced, curved the board into a V and slid the tiles from the last game into the old red handbag we used as a shakeup. The way she did it, her long hair angling over her yellow tie-dyed shirt, she was purposeful and pretty, a Wyeth painting. He didn’t deserve her. Treufel leaned the crab over the bag and tried to make it pick out a tile like it was a pair of chopsticks. He made the high-pitched sound of his crab-alien beast, “Nrreee-eeee!”

“Stop that, Eric!” Janie clamped the bag shut.

“Nrrreee-RUFF!” Now apparently it was half-crab, half-dog.

“Stop it! You’re not being funny!” Treufel rose from his chair and began menacing her with the thing. I whittled my chain. The best way to start a screaming fight in our house was for Beck or me to interfere with whatever our sister was trying to do.

Janie gathered her calm, unfolded the board and placed it in the middle of the checkered red oilskin. “I say we’re going to put the crab aside for now and play a nice game of Scrabble.” I wondered how disputes of this sort were settled in the Treufel household. Probably with shouts and a clip across the ear.

Treufel stood the crab in the middle of the board. Janie’s slim arms dropped to her sides in frustration. My guess was, Eric had never seen a Scrabble board, wouldn’t even know how to play. Janie should have showed him without implying she was teaching him something. If you corner something wild, my dad told me when I took our cottage trash to the dump, you make it more dangerous. Scrawny brown bears foraged among the torn plastic bags and burning paper, addicted to our Wheaties and frozen waffles. You have to step wide around a dumb thing, he said, leave it a chance to escape with its dignity.

Treufel slid the crab around the board like a bumper-car, making tire-screeching noises in the corners. Anastasia bent over her magazine in the shadows. I wanted to take her by the hand and say, save your babysitting money, seriously. Get out as soon as you can, run – my mom can tell you how. At that moment, with our dad not here, with Beck in his Banana Splits shirt staring wide-eyed between Janie and her boyfriend to see if he should laugh, I felt the close balance of power that permitted bullying, the lack of a firm hand that already suggested how this would end.

As her boyfriend made up new crab noises, Janie gave up trying to be practical, held the shakeup bag to her chest and keened like a child, “Mo-om!” Our mother walked over from the sink, wiping her hands on her apron. “Come on Eric, we’ve had enough of this, it’s time to clear the table for dinner.” She held out her hand like a teacher demanding a kid’s chewing gum. Treufel leaned back a second, like even he knew when enough was enough. Then he gave his head a defiant roll and snapped the crab right in her face. Mom’s eyebrows came down and her eyes went to small black dots. Janie gasped, the only unfeigned gasp I believe I’d ever heard.

“The human mother!” Treufel growled, waving the thing’s claws at her. He still didn’t get it. I took in a breath and held it. Anastasia touched her hands to the sides of her face. Mom grabbed the shell. “Don’t!” he yelled in a surprisingly adult voice, the playfulness gone. He bounced up into a boxing stance. For a moment they stood toe to toe. Then he took her wrist and pulled her hip-first into the folding table, which rocked onto two legs, nearly pulling my mother over and spilling Beck’s pan of water across the floor.

Janie looked between the two of them, boyfriend and disapproving mother, trying to decide where lay the larger grief. This was the boy she’d spent a good part of her energy for the last month defending. My mother ran both hands down her threadbare apron and looked Treufel in the eye as he repeated his stupid crab sound. “Eric Treufel, you’re a willful creature,” she said, out of breath for such a brief confrontation. “And you’re all set to follow your brothers, both of whom are low-life scum.”

I’d never heard such harsh words from her. Her anger was clumsy, unpracticed. I thought he might sneer at her softness, at her clear underestimation of his devil-may-care resolve. But the laugh fell from Eric’s face like ice shucking off frozen shrimp. His arm went weak and the crab fell on the floor. I could see the welt where it pinched him, or where he’d been pinching it to himself. He sat at the Scrabble table and began to cry, his face and the red weal hidden inside folded arms. His sister went into the bathroom, bent forward, her wild hair curtaining her face. Janie settled next to me on the couch, lips drawn back, blue eyes staring like she was sitting in the recovery chair outside the nurse’s office. I had the crazy idea she might try to grab my whittling knife. I closed the blade into the fake stag horn handle.

The crab ambled across the floor in no particular direction. Beck looked between the spilled water pan and our mom, who went back to scrubbing yesterday’s spaghetti off the aluminum strainer.

After a minute, Eric banged to his feet, grabbed his jacket from beside the door and stormed out into the dark. A moth bumbled in. Mom lay the strainer over the wooden drying rack I’d made in shop and went into her bedroom. After a while, she came out wearing her coat, said, “All right, pack it up,” and we began the drill of gathering our stuff. We could hear Anastasia in the bathroom blowing her nose.

There were no streetlights on the road for the last seven or eight miles to the cottage, just the round red reflectors on the snow-height marker poles, blinking as we passed.

Eventually our headlights picked up Treufel in his jeans jacket with his thumb up. When he saw it was us he dropped his arm and resumed walking. Anastasia pretended to be asleep on the lay-down seat. Janie lowered her window and leaned out into the cold air. “Come on, Eric, it’s fifty-five miles!”

“Only fifty now,” he huffed, overestimating his reach as usual. “Tell your bitch mom us scum are tough.” Mom’s face hardened and she stepped on the gas. “Mom!” Janie pleaded. We flew down the road another two hundred yards then lurch-stopped.

Our mother looked up at the ceiling, shaking her head. She put the car in Park. Treufel trudged past, face down, his breath surrounding his head. In the back seat I looked supportively at Janie, who rubbed her palm from her lip upward to her nose. She’d had a rotten weekend and the next few days at school weren’t going to be much fun.

That was when Beck twisted around in the front seat, clasped his hands together, elbows high and out, feigned a bright cheeriness and said, “So! Only two more of these and you’ll be getting married I guess!”

Janie’s mouth dropped. Beck held his goofy posture but his eyes betrayed quick terrified uncertainty. I reached out to put a hand on Janie’s arm, to say hey, he’s twelve, don’t let’s make it worse. But to my surprise she laughed. At first a hapless blurt mixed with tears, then she was laughing at the fact she was laughing and unable to stop. Beck and I started too, then even our mom. Poor skinny Anastasia was making noises underneath her coat. “Don’t! Stop,” Janie cried, “I’m gonna pee!” and we laughed even harder. “Oh boy,” Beck said, straining for breath, “I sure wish that crab was here to see this!” He’d taken the thing down to the dock and lowered it carefully into its familiar dark. Our mom’s shoulders shook. With one hand over her mouth she gave tiny ‘no-no’s of her head, like this is awful. This isn’t how you’re supposed to run a family.

We couldn’t see Treufel any more. I knew there was no way we could force him into the car. Mom wiped her eyes with both palms from the middle of her nose out to the sides and said, “Okay now. Quiet down, all of you. Not a word about this, do you hear me? Not a single word from anybody. Get it all out of your system now.” She took a long breath, blew her own laughter out like a candle, fixed-on a serious face the same way she’d probably tried in a tall mirror before walking out forever on her first family, and put the car in gear.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.