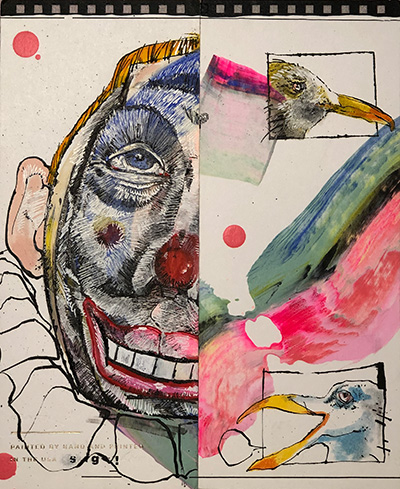

Illustrated by Scott Gandell

I met Adam at the bookstore. He was in the section marked Biography/History and he was looking, extensively, at a book about some historical event no one’s ever heard of. The only way I knew it was an historical event was because the cover was in black and white and had a photo on it of a tank. But it wasn’t a World War II book; WWII has its own section, way over on the other side of the store.

I myself was aiming for the art books, because my friend Terrie had just had a life-changing experience from looking at a photograph of a clown. She’d spent her childhood terrified of clowns but when she saw this photo, on a friend’s coffee table, she experienced a 180 degree shift– one of those rare moments when the other side becomes clear as anything, and we can no longer understand why it was so hard to get before.

“Clowns are desperate,” she’d told me, with wonder in her voice. “That’s why they’re so scary.”

It hadn’t occurred to me either, and I wanted to see if she was right. I too had had the experience of a childhood clown doll that one day had transformed from delightful toy-friend into the diabolical engineer of my nightmares. It had to be sold at the neighbor’s garage sale, because I refused to sell it at my own. Someone bought it for seventy-five cents–some kid too young to feel the fear yet–and I threw the cursed coins into the outdoor trash, observing as the other neighborhood kids spotted and retrieved them. Let them spend it, I thought, from the safety of my bedroom. It will only bring them grief.

They used the quarters to buy ice cream.

Story of my life.

I found the art book Terrie had been talking about, and flipped towards the photo of the clown, which, according to the table of contents, was on page 32. As I skipped through those shiny pages, pages that smelled like a hair salon, Adam turned and held up the war book. “Do you know this photo?” he asked me, tapping the cover.

“Oh,” I said. “Is that World War I?”

He shook his head, and his hair was very light brown, almost colorless, and as it shifted, it caught no light.

“Korean war,” he said. “A photo from then.”

“Mmm.”

He shelved the book. “They told me it was a good read but I just read a page and it was so dull,” and then he stepped closer. Aside from that colorless hair, he had a wide open face, sort of big-featured, with a big nose and big eyes and teeth. Likeable. The kind of face you could immediately trust, even against better judgment.

I held my finger before page 32. I didn’t want to look at the clown first off. It seemed too intimate, even if I was just looking with myself. So I was looking, then, instead, at a washed-up movie star wearing sequins in some kind of aquarium tank emptied of water. I guess they were trying to work with the phrase ‘washed up’, but the star didn’t seem aware of that because she was grinning in the tank like it was all funny and fun. Maybe the whole book should’ve been titled desperation.

“What are you looking at?” he asked, peering over my shoulder.

“Art photos,” I said.

“Wait, wasn’t she in that cop movie?”

We stared at her together, in that tank. “Was she?” I asked. She had giant breasts, ornamented by magenta sequins. I found her painful, so I turned the page to have something to do, and there was the clown, with its big nose and scary mouth makeup and scary eyes and red costume. And I could see what she meant, Terrie. Right off, I got what she was saying. It was trying so hard. That was part of what was so menacing–its enormous effort to amuse. You kind of wanted to hurt the clown, before it smothered you into total suffocation.

“Do you think it looks desperate?” I asked him.

He squinted his eyes, and stared at the photo for at least a minute. “Why do they do the eyes like that?” he said, at last. “I mean, the star-shaped thing? Is that clown protocol?”

We ended up at the Greek coffee place next door, and he bought no biography and before we left the store, I flipped through the rest of the photo book to see if the others were desperate too but they weren’t, not in the same way. They were just pictures of other shiny figures that looked good in bright colors, like Vegas acrobatic performers at Rite-Aid, or a tomato farmer in his garden reading Newsweek. Only pages 30-32 were terrifying.

Adam got up to get the coffees while I looked out at the cars driving by on Sunset. It was raining a little, and watching the windshield wipers made me feel more settled. The air smelled like damp city.

“They told me that was the definitive book on Korea,” he said, returning with the coffees. “I’m disappointed.”

I felt attractive, talking to him. Next to those big features of his, I could feel myself as delicate. When the conversation waned, I sipped from my bitter little Greek coffee, and told him that my friend Terrie was having surgery the following day. That she was young, still, but they’d found problematic shapes in her bronchitis x-ray. “Lumpy shapes,” I said, “inside her lungs.”

He stirred his coffee, and nodded with appropriate solemnity. He seemed more measured, now that he was caffeinated.

The cars whisked by.

“You know,” I said. “I just lied. That’s not true.”

“About Debby?”

I reached out, and touched his arm. “I didn’t know what to say,” I said, and his arm was warm, “so I made up Terrie’s lumps. That’s awful of me.”

He leaned in, then, and he didn’t kiss me but it was too close for regular. We spent a few minutes there, blinking together, breathing the coffee-scented air. Who knew what would happen? He had that trustworthy face, a face I didn’t trust, simply because I’d trusted it so swiftly.

***

We agreed to meet the following afternoon at the beach in Santa Monica, and the directions we gave each other were complicated enough, were distinct enough, so neither could possibly get lost. Of course I was early because I’m always early, and I didn’t head over to the water just yet, instead wandering past the snack bar, reading the names of foods listed in black plastic stick-on letters: chili dog. Onion rings. Popsicle. Words I love to see in black plastic stick-on, words that conveyed summer to me, on this cloudy November afternoon. I hadn’t called Terrie the night before, because I’d sold her out for flirting; it seemed I’d cursed her, and although I was fairly certain I had no cursing abilities, it was not in the spirit of good friendship and this I knew. But I had not been flirted with in many months, and this man had not rejected the reeking desperation of either the clown or the old star, and asking for sympathy about a dying friend was the first tool that appeared from my own personal flirting toolbox. Sometimes my own capacity for smallness is surprising, even to myself.

Adam was already at the beach when I walked over, and he had a picnic basket in his hands. He’d set up a blowzy checkered blanket, whose corners picked up with the wind, and when I walked across the sand, bumpy and difficult to traverse, he smiled at me with those wide open eyes. For a few minutes we chit-chatted, and at one point, he threw his hands into the air and said some exclamations, about nothing, really, but just showing a sense of spirit. I felt the love, spreading roots in my chest, making it so easy to smile, the way the promise of love loosens and eases the muscles of the face, and how the onset of pain had tightened them before, into tense lines and grit. How good it felt, to let go of grit for a second! We settled onto the blanket and he opened a small size bottle of champagne and we toasted and the water waves crashed, and other than a homeless man way to the left and two teenagers trying to get tan on the right, we were alone. I reached out a hand, and touched his colorless hair, and he turned his face to my palm. Then he reached into the picnic basket, and pulled out two plates, two checkered napkins, and two forks.

“Wow,” I said. “You go all out.”

As he removed the plastic food containers, he told me he used to be a chef, that he used to own his own restaurant. He told me the name of it, and how he’d gotten a great review last year in the L.A. Weekly, saying he had a knack for unusual flavor combinations. “Really?” I said, impressed, and then, after a pause, he said no. “I mean, I’ve always liked to cook. Never got paid for it. Sorry.” We looked out at the water. It was the second lie, and it was clear, from the tone of his takeback, that he had surprised himself with it. For whatever reason, it seemed we couldn’t help but lie to each other. It didn’t even feel like a big deal to me at first, but like an unexpected shift in weather, as the food came out of the basket, his mood collapsed. When he removed pieces of a roasted chicken from the container, and handfuls of green grapes, they were almost like apologies, for something he had committed long ago and I would never understand. Certainly he had no reason to apologize to me, me who was so ready to love him. He handed me a charred chicken leg, and a bunch of grapes, and refilled my champagne. “It’s lovely,” I said, about five times, but he wriggled under the compliment, and wouldn’t look over, and the way he sealed the remaining food back into its containers, with careful palm and thumb, made me feel badly, as if I’d done something wrong, or as if we both knew, in the future, that we would wrong each other irreparably. The seagulls approached. I ate the chicken and grapes, peeling stripes of chicken off the leg, but everything tasted a little off. Not like poison, but just not fulfilling, and Adam was striking me now as very difficult to know. “Why’d you want that book?” I asked, as I peeled the skin off a grape in slippery little triangles, and I understood then that I would be undressing every item of food I could because my clothes would be staying on.

“I like war books,” he said, out to the ocean. “Of wars people don’t read. I like to remember the forgotten wars.”

For dessert, he brought out oatmeal macadamia cookies that he had baked himself, but I could hardly eat them, my mouth felt so dry, and without thinking, I threw a few sprinkles to the seagulls who stepped closer on their webbed feet. I slipped my whole cookie into the sand when he wasn’t looking. Adam and I walked to the water and held hands and touched our bare cold toes to the foam. I felt like crying, then, with those seagulls invading our perfect picnic behind us, eating the cookies and the chicken, stepping all over the napkins, cackling, shoving each other out of the way.

I touched his arm again, and my eyes filled with tears.

“I know,” he said. “It isn’t right.”

When we finally kissed, it was clear that it was our last. His lips pressed gently against mine. I felt that kind of wrenching in my heart, and as I turned and walked the other way, I could hear him packing the picnic back into his basket. It took some effort to shoo away the seagulls, but finally they squawked and flew over us. A flock of seagulls. As a child, I’d found them so wonderful, seabirds, with their curving yellow-orange beaks and funny strut. They lived at the ocean, and anything that lived at the ocean I felt I could love forever. But they turned, in my mind. Sometime around adolescence, after hitting the critical mass of beach picnics, after seeing them come over again and again, pushing each other out of the way, squawking so loud, eating chicken and turkey sandwiches without pause, I found them repulsive.

At the snack bar, I ordered a basket of onion rings and sat on the green-painted ocean bench, watching the water. The clouds were thick, and the water took on a metallic gray sheen that eased my mind. When Adam passed by, with his picnic basket all packed up, I nodded, and he nodded. The look he gave my onion rings was that of a betrayed lover. But I have always liked onion rings. They were the thickly-cut kind, each ring the width of a plastic bracelet, dipped in golden-brown crumbs. I ate almost the whole basket, licking the bits off my fingers, and when I was done, I threw the remaining few to the trio of waiting seagulls, who, after all, were only hungry. Opinions change.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.