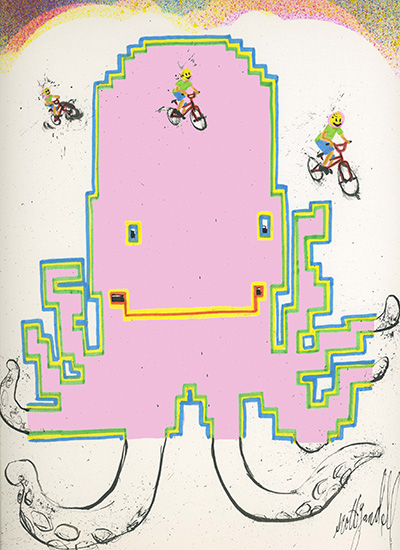

Illustrated by Scott Gandell

Between the fourth and sixth grades, you are seized by three deep and compulsive obsessions:

Marvel comic books (all things Daredevil and X-Men and Spiderman)

BMX bicycles (yours: a secondhand Mongoose, unwieldy and spray-painted black after you stripped the frame down to its bare chrome-moly tubing)

Video games

Your parents find all three activities dubious. Comic books are allowed because they get you reading something besides MAD magazine, and therefore seem remotely educational. And when you’re on your bicycle, you’re out of the house, out of your parents’ way. You’re doing something sort of athletic, even if the extent of this athletic activity is you and your friends racing up and down Parkway Avenue, seeing whose tires can leave the longest skid, and assembling ramps from plywood scraps. (One day, your friends will shove a few extra bricks under one of these ramps, raising it higher than they’re willing to attempt, and you won’t notice. Moments later you’ll fly higher and farther than ever, sailing beautifully, historically, over lengths of sidewalk, and then you’ll crash into the low brick wall dividing the Delgado and Murillo properties, knocking the wind out of your lungs and fracturing a rib that will then bend forever outward.)

Your parents are most resistant to video games because they have no redemptive value. A waste of quarters. A waste of time. You are not allowed an Atari. No Intellivision or ColecoVision either. The closest thing you have is a nameless knockoff, presented one Christmas by your estranged grandfather. (His presence in your life is shadowy and distant; he does not know about video games being unwelcome.) This beige console lets you play three blocky, black-and-white variations of Pong. Since you already know the good stuff, it entertains you for less than an hour.

There are the arcades: Chuck E. Cheese on the north side of town; Showboat in Puente Hills; and, somewhere off the 605 freeway, Golf ‘n’ Stuff Fun Center, which you’ve never visited and yet which exists in your elementary-school imagination with a golden, mythological glow. And you have also played interesting, solitary video games in other places: Track & Field at the Santa Fe Farms liquor store; Jungle Hunt inside Crawford’s Market; Tempest—a confusing waste of quarters at the Food Barn on Ramona Boulevard. But it is the Golfland arcade that has collected your favorites all in one place.

Spy Hunter.

Star Wars.

Zaxxon.

Pole Position.

Gyruss.

PunchOut!!

Golfland becomes the center of your universe. It is adjacent to the 60 freeway’s Peck Road off ramp, so whenever you go anywhere with your parents, you’re welcomed home by its four miniature golf courses, by their bright green and yellow dragons, their expressions silly and slightly crazed.

At this point, you’re too young to notice girls, though you already sense that unless you’re on a date or need to entertain younger cousins, you won’t ever really give a shit about mini golf. Instead you will commit the location of the video games inside the arcade to memory. Wall after wall of them, the space dimly lit by the flashing screens of the machines, the air somehow smoky in your recollection. To be at Golfland is to do something outside of your parents’ approval. This is your first taste of rebellion. The thrill feels seedy and vaguely self-destructive, the nascent equivalent of being in a casino, a nudie bar, and a street fight all at once. Each week, you are drawn there with the sort of magnetic, gravitational pull experienced by wayward meteors and doomed astronauts returning to Earth.

* * *

On Friday evenings, usually after dinner, your father takes out his money clip and hands you your allowance. For helping with the lawn, dragging out the trash cans, and picking up the dogs’ shit all week, you receive five dollars. He enjoys telling you not to spend it all in one place.

On Saturday mornings, your mother turns the bathroom into a hair salon, her clients a few holdovers from her former life as a beautician. The ladies arrive early and are there until the middle of the day, the house filling with the acrid smell of permanent-wave solution, with the steady noise from the salon-style hair dryer that sits on the kitchen table and fits over their heads like a golden space helmet.

Your father works every weekend. (While he’ll claim that Saturday money at time-and-a-half, double-time on Sundays, is too good to pass up, later on you’ll have to understand that he simply preferred his life at the supermarket, a life where he was free to order everyone around as he pleased.) He leaves before dawn, and he doesn’t return until your mother’s ladies have gone.

This is why you’re free to roam around on Saturday mornings. Golfland opens at 10, and if you’re not out of the house by 9:30, you feel hopelessly behind schedule. You tell your mother that you’ll be back, choosing a moment when she’s too preoccupied with operating a curling iron or applying hair dye to ask where you’re going. You retrieve your bicycle from the shed where the lawnmower is stored. You wind the length of duct-taped chain around the seat post and secure it with the fat Master lock. You leave through the side gate, stomping your feet at the dogs to keep them inside.

These morning rides are crisp, the air cold against your forearms, your hands starting to ache. (You don’t have the black, knit gloves that you’ll eventually copy off the riders in BMX Action, and you can’t ride with both hands in your pockets instead of on the handlebars.) You pedal west on Parkway, the lock knocking against the frame as you pedal, the sun at your back, low and bright. You continue until the street ends.

There you veer onto the bike path, the San Gabriel River to your left. In the summer, the riverbed reduces to a series of stagnant puddles. In the winter, collected rain rushes past sandy islands, overturned shopping carts, and clusters of leafy bamboo. The water cascades over concrete retainers meant to slow it, and it eddies around bunches of wild carp. Sometimes you spot a crane, a shard of white against the green, before it opens its wings and leaps effortlessly into flight. Aside from the occasional team of ten-speeders, who blur past in a whiz of neatly clicking gears and coordinated blue Lycra, you are alone.

When you reach the 60 freeway, you are minutes away from Golfland, and your excitement is uncontainable. The trail dips downward and you pedal your hardest, gaining double speed. When you’re under the freeway, the unceasing roar of cars overhead, you shout as loud as you can.

* * *

The sound of four quarters falling out of a change machine is a delight, and the jackpot sound of 20 quarters falling after you’ve inserted a five-dollar bill is rapturous. If Golfland’s change machines produced tiny snacks instead of quarters, you’d be salivating. Even though you’ve gotten there early, other kids are already crowded around the games you’ve waited all week to play. In the fourth grade, there is no statement more bad-ass than the placing of a quarter at the edge of a video-game screen. The tap of the coin against the glass declares that you’re playing next. It also implies that you will play the game better than whomever is at the joystick, and your looming presence over their shoulder will insist that they get it over with already.

You are not bad-ass, so you walk around until your opportunities come. When they do, you love the digitized versions of Bach and Henry Mancini used as theme music, the robotic voices asking that you prepare to qualify, the different chimes and chirps that signal incremental accomplishments. A bracing thud as your spacecraft is equipped with double cannons. A high whine when you shift into high gear. The hyperspace trill bringing you one warp closer to Earth. You love the idea of your lasers winging Darth Vader’s Tie Fighter and sending him spinning into space as you advance on the Death Star. You love the challenge of destroying your enemies before they can destroy you.

Of all the games, PunchOut!! is the one you love most. It lets you be a boxer, your green character looking something like a graph-paper diagram of Bruce Banner half-transformed into the Hulk. After you drop in a quarter, the game asks you to enter your initials, to declare an identity before your first match. Sometimes you get brave and put M♥V. Most often you are MIK, ignoring that the E won’t fit.

Your fourth-grade sensibility finds the opponent characters intriguing. Glass Joe is goofy; and Piston Hurricane seems tough; and Bald Bull, who reminds you of Marvin Hagler, repeatedly reveals your lack of hand-eye coordination with his devastating uppercut. You infrequently make it to a fourth fight. Each time you manage one, Kid Quick lives up to his name and dispatches you with a relentless flurry of punches that you are helpless to counter. When you go down, his pixilated taunting prompts another quarter into the machine.

It will take you a while to realize the secret of your opponents’ eyes flashing yellow right before they try to punch you. When you are knocked down, the game will encourage you to get up, and in an effort to regain strength, you will tap the left and right buttons as fast as you can. You’ve seen other kids do it, but you don’t know if it actually works.

There will be the occasional game when it all comes easy, when you lock in on the pattern of each opponent, and their special move doesn’t faze you. You will avoid their jabs and hooks and body blows and strike back with purpose, your strength gaining. When it peaks, the right-hook punch enabled, the game will tell you to put your opponent away and you will.

(Many years later, you will begin dating a girl who loves vintage clothing and art-deco furniture. Holding hands, you’ll notice that she has a permanent callus that she calls her Nintendo Thumb. There will be a subsequent afternoon when her brother dusts off their old system, and with Mike Tyson’s PunchOut!! in the console, the girl will proceed to easily defeat the game’s opponents, the muscle memory in her hands still sharp, her reflexes instinctive and automatic. On her first try, she will take down Glass Joe, and then Von Kaiser, Piston Honda, and then Don Flamenco, King Hippo and Great Tiger and Bald Bull. It will be one of the most pure and beautiful displays of skill that you’ll ever witness. Ultimately she’ll lose to Mr. Sandman, an opponent that you hadn’t actually seen before then. You’ll want her to keep going, only she’ll be bored by the game and will set the controller aside as if it were an empty glass or an old magazine. The memory of her turn will nevertheless remain and it will become one of the many reasons you ask her to marry you.)

* * *

You are not a great video-game player. You are not even good. Only sometimes, when a magical game occurs, will your name make it to the high-score list. This is the opportunity Golfland offers you. A chance to be recognized. To make your mark. No matter if that mark is just three letters in the middle of a list of 50 other scores, if the recognition is essentially the final command in a computer program. It does not matter that your name will disappear when the machine is unplugged. This moment, this illusion of being accomplished at something, is the exact moment that you had hoped for. When it happens, you will wait for the screens to cycle through so that you can see your name again.

When your pockets are finally empty, you will check the game to see the high-score screen one last time. You will then head down the long hallway that leads to the exit. The cacophony of all the games going at once will echo off the orange tiles, and it will make you miss the arcade before you’ve even left it. Outside, you will unlock your bicycle and regard the vast, hot stretch of asphalt that is Golfland’s parking lot, blinking at the midday sun as if you’ve emerged from a cave. Your trip, like many of life’s narcotic pleasures, has been intense and is over quickly, but it will seem like a big part of the day has gone by without you. By now you’ll be expected back at home. You’ll take your time getting there.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.