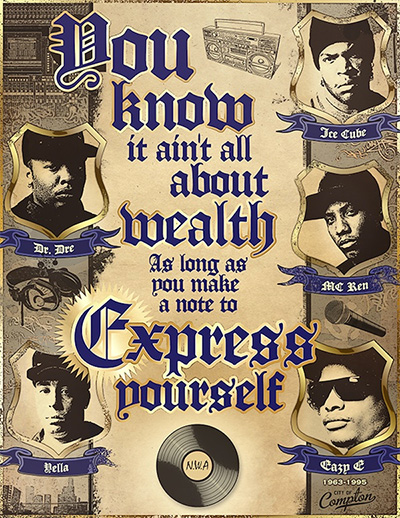

Illustrated by Patrick Sean Farley

August ’88: Eazy E props his Air Jordans up on a desk, stares at the ceiling, and leaves the room whenever the beeper on his belt goes off, which is often. He answers most of the reporter’s questions with a noncommittal mmmmm; he could as well be talking to a parole officer as a writer from the slicks. Eazy’s group N.W.A — Niggas With Attitude — has just finished mixing down “Gangsta Gangsta,” a breathtakingly violent, vulgar gangster-rap jam that is their first single in more than a year. In the office of the record company president, Dre, the producer, slaps in a tape; it’s the first time anybody has heard the song outside the studio. Ice Cube’s angry voice cuts through the room over a funky Steve Arrington guitar riff: “.?.?. Out the door, but we don’t quit./Ren said, ‘Let’s start some shit.’/I got a shotgun, and here’s the plot:/Takin’ niggas out with a flurry of buckshot .?.?.”

Fifteen sets of jaws go slack, including their manager’s, their publicist’s, and the president’s. Fifteen sets of eyes stare at the carpet, the ceiling, the California Raisins gold records on the walls, anywhere but the cassette deck. The white people look shocked, the black people embarrassed. A drive-time jock rubs his temple hard. One promotion guy cackles in the corner, muttering, “I love to work dirty records. I love to work dirty records.” Eazy smirks. The hooks are tight, the rhymes are tough, the rapping right on key — it’s a perfect hardcore rap track .?.?. and unthinkable.

February ’89: On the morning his solo record was certified gold, Eazy E stood blinking in the well-kept backyard of his mother’s house in Compton, 15 minutes south of downtown. He is tiny, his neat Jheri curls just so beneath a black Raiders cap, the gold chain around his neck thick as his frail wrists. He slouched, eyes puffy, as if his body couldn’t believe it wasn’t still in bed. He and his friends in N.W.A had hung out at a Bobby Brown gig, holding court, until late. Two days earlier they had hosted a segment of Yo! MTV Raps (though MTV would refuse to play their video); later that afternoon they will be interviewed by Word Up!, a black-teen pinup magazine; the next day they will fly to New York for something called the Urban Teen Awards.

Eazy, who signs checks as Eric Wright, is sole owner of Ruthless Records, an independent hip-hop production company that releases music through Atlantic, Elektra/Asylum and Priority, a compilation label run by a former K-tel executive who had never before dealt with an act, unless you count the California Raisins. The Ruthless touch, the raw, danceable Compton street sound, is hot, and each of the label’s three Dre-produced rap albums — by Eazy, N.W.A and J.J. Fad — is certified gold, well on its way to platinum. This spring there’ll be three more, plus an unexpurgated N.W.A video album and, for squeamish retailers (and the armed services), a self-censored version of Straight Outta Compton minus “Fuck tha Police,” half the violence and all the cuss words. (The censored version of Eazy-Duz-It reportedly accounts for close to 200,000 of the roughly 900,000 copies sold.) The final figure hasn’t been released yet, but Ruthless is rumored to have shopped around the Dr. Dre–produced album by rapper D.O.C. for a cool million, and Sylvia Rhone of Atlantic A&R snapped it up. When this summer’s projected tour with Ice-T fell through last week, Eazy arranged a 60-city Compton Posse tour himself, with N.W.A headlining over MC Hammer and Too Short.

Each of the five members of N.W.A writes songs for each of the Ruthless albums, whether dance, rap or squishy soul. Each member of N.W.A — young Compton men who all grew up in the same couple of blocks — will probably earn in the six figures this year. Eazy’s manager, Jerry Heller, who was instrumental in breaking Elton John and Pink Floyd, supposes $75 million in retail sales for Ruthless next year might be about right, and thinks Eazy might be the most important black-music entrepreneur since Motown’s Berry Gordy.

“I’ve been in the music business 30 years,” Heller says. “Eazy is the most Machiavellian guy I’ve ever met. He instinctively knows about power and how to control people. The couple of times I’ve gone against him, I’ve been wrong. And his musical instincts are infallible. In a few years, Ruthless could be as big as A&M.”

Today, N.W.A is being photographed. “If this is going to be on the cover, we should find us an alley or something,” Eazy says. “Man, if we get us in an alley for this picture, niggas gonna know we drove to an alley in a Benz,” Ice Cube says. “Let’s do it right here in the back yard.”

They pose, first by the stagnant green water of a fountain, then near some steps, assuming a formation familiar from every published photo of the band.

“What, no AK?” somebody asks. Eazy looks disappointed. “Shit, man, this is my mother’s house. All that stuff is at my place.” He straightens from his crouch and goes inside. A minute later he reappears with a heavy-canvas duffel bag and empties weaponry onto the grass like a Little League coach pouring out bats and balls — 9-millimeter repeating pistols and 12-gauge shotguns and a couple of small-bore rifles and a .38 and a mean-looking sawed-off, clips, sights, scopes and boxes of ammunition, an arsenal bigger than Sergeant Samuel K. Doe needed to overthrow Liberia. But no AKs. Not at Mom’s house.

N.W.A swarms over the guns: “Give me the revolver, man .?.?. Put in the gunpowder, boom. Give me the scope, man .?.?. No, man, that’s a BB gun, ain’t nothing in that one .?.?. That one is an ugly motherfucker right here, man, you got to hide that, yeah .?.?. John F. Kennedy. John Fuckin’ Kennedy — that scope is def.”

Click.

“You look like an orange, like something up at the range .?.?. Those scopes with the little red dot is hard .?.?. What’s that got? .?.?. One of those Public Enemy things in there, the crosshairs .?.?. Give me the nine, off with this motherfucker .?.?. What you mean, man, that’s a magnum, that shit look kind of crazy .?.?. I be like comin’ from the hidden, still be comin’, pop you off right in the ditch .?.?. Pow! This shit is kickin’. Roll over and die, motherfucker.”

Click. Click-click. Click. Click.

“Hey, Eazy, your momma give you this Daisy-ass shit? .?.?. I can really shoot you, right? .?.?. Crispus Attucks .?.?. No, man, never hold it where you can only see the scope — that’s a long-ass shotgun. Get it right, soldier. I want your ass .?.?. I need that ass .?.?. I want your radio. Ten guns, sheriff guns, chrome guns, shotguns, old black movies .?.?. You see the smoke and the bullet.”

Click. Click-click. Click. (The photographer shoots back.)

“Public Enemy uses plastic guns, you know,” Ice Cube says.

A black person in leather with a gun is considered bad, crazy hard. But I’m not saying so much “Fuck the police” as “Let’s grow up more.”

—KRS-One, June ’88

Fuck tha Police!

—N.W.A,October ’88

Public Enemy is hard. Too Short is hard. Eric B. and Rakim are hard: raw, noisy, uncommercial. Hard beats are what you hear pounding from Oldsmobiles, boomboxes, skateparks and hardly ever from the radio; spare, percussive backing tracks composed with cheap-sounding drum machines and short snatches bitten from old soul singles.

L.L. Cool J used to be hard until he recorded a love song, which no self-respecting rapper will ever let him forget. Run-DMC were hard until they jammed with Aerosmith. KRS-One of Boogie Down Productions, whose first album included an ode to his 9mm repeater pistol, wanted to stay hard so bad that he posed with an Uzi on the cover of his last album — an album whose hit single was “Stop the Violence.” The brutal calculus of hardness forgives lapses in taste, but never in form. “There’s a principle involved,” Ice Cube says. “The Weekly wouldn’t run a picture of a baby getting its head cut off; N.W.A wouldn’t do a pop song.”

Hardness arose as a rap aesthetic at about the same time much of the music became essentially suburban. While artists from Harlem and the Bronx were still producing good-time party jams, middle-class kids from Queens and Long Island began to form the contemporary image of the rapper as an articulate gangster with a chip on his shoulder, a young black man hard by choice. (Every rapper suburban middle-class Def Jam mogul Rick Rubin ever had a hand in producing is hard: Run, L.L., PE, Slick Rick, even the Beastie Boys.) Hard rap, like punk, brought together a self-selected community of kids by becoming an image of what their parents feared most.

L.A. hip-hop had been the Next Big Thing for years, but the proto-hi-energy sound — bass-heavy, fast tempo, ticky-ticky-ticky synthesizer clicks, heavy breathing and moans straight out of the Barry White songbook — was the opposite of hard. It meant more for the flygirl in the disco than the homeboy on the street corner. Ice-T, a Crenshaw High grad who still billed himself as a transported New Yorker in the mid-’80s, was the first to realize that if pretend gangsters went over so well, a niche existed for the sort of real gangster he’d been in his early teens. He performed with one fist wrapped around an Uzi, released a 12-inch (“Killers”) he knew was too hard for the radio, and spent a lot of time getting his picture taken near picturesque, graffiti-spattered walls in South-Central L.A.

If Ice-T’s pose was a little calculated, his approach to rhyme closer to pastiche than innovation, he still developed a national reputation as the hardest rapper in the business. He moved hundreds of thousands of records while such overhyped local electro-hoppers as the Dream Team and the World Class Wrecking Kru floundered. The members of Uncle Jam’s Army, who had regularly thrown hip-hop parties at venues as large as the Sports Arena, had long since dispersed. Gangster style quickly replaced slick surface as the hallmark of the L.A. sound. And as Ice-T grew avuncular with age, up came younger, harder and more street-wise rappers to nudge him to the side of the stage: Tone-Loc (whose hardness didn’t last all that long); King T and DJ Pooh; and especially Easy E and N.W.A, who came across as active gangsters, not world-weary alumni.

In ’86 Ice Cube, then a 16-year-old neighbor and follower of the Wrecking Kru, wrote a cussword-packed song for HBO, a long-forgotten New York rap posse, who rejected it as too West Coast. Dre, the Kru’s DJ, along with his aide-de-camp Yella, convinced his neighbor Eazy to try the rhyme. E put on a pair of dark shades, ejected his friends from the studio, and rapped for the first time. Later, he sunk a few thousand dollars into getting the 12-inch record pressed and released.

Depending on who you talk to and when, the seed money may or may not have come from illicit drug profits. Last August, Eazy asked me where I thought he got it. Last week, Dre refused to comment. Ren said, “Eazy had a cousin that was runnin’ everything around here, man, and when his cousin got killed, he was left with all these responsibilities of the street. So many people was getting killed, I guess he realized he had to get out. He invested his money, you know, in the record business. Like he says, that’s no myth.” Eazy silenced him with a glance.

“I know the drug thing sounds glamorous, but I wish they wouldn’t keep saying that,” Jerry Heller says later. “It wasn’t all that much money. And IRS guys will read this thing, too.”

“Boyz-N-the-Hood,” five and a half minutes of cheerful vignettes from the short, happy life of a ghetto hoodlum, became the cornerstone of the California street sound, one of the first West Coast rap records rooted as much in the hardcore New York break style as in Kraftwerk. Eazy’s rapping is a drawling blend of Woody Woodpecker and the vicious, whiskey smooth tenor of Rakim: a superb character voice. The song was considerably slower than the party jams put out by local groups like the Kru and the Dream Team, and the production was knowingly raw — you can pick out Dre’s tinkly two-note keyboard riff and exuberantly tinny beatbox coming from a car radio two blocks away. A lot of people hated the record, because while the urban-gangster life had been romanticized since Capone, nobody had ever made it sound quite so much fun before.

“It is fun,” Eazy says.

N.W.A got an opening slot on the West Coast dates of the Salt-N-Pepa tour in the fall of ’87. KDAY, the local hip-hop station, put “Boyz-N-the-Hood” into rotation before the L.A. date, and the record was requested often enough to jump to No. 1 on their playlist for almost a month. Ice Cube wrote two more: “8 Ball,” a paean to his beloved Olde English 800 malt liquor, and a sneering cautionary tale called “Dopeman,” both of which were released as the first double-sided N.W.A single. (Basically, an Eazy E song ambles, while an N.W.A song cranks: the performers, producers, writers and sidemen are identical.) That 12-inch also sold well.

Macola Records, the distributor, collected 10 or so random Dre-produced sides and packaged them as an unauthorized bootleg N.W.A LP, N.W.A and the Posse, that stayed on the Billboard black album charts for the better part of a year. (N.W.A refuses to discuss this album; more than the money, the dated hi-energy cuts, many of which Eazy originally declined to release, embarrass them.) Macola settled with Ruthless out of court for legal fees and damages but, according to band members, still pays the installments with rubber checks. (“They ganked us, man, straight fucked us with no grease,” Eazy says.) After this, Ice Cube left the group for a year to study mechanical drafting.

Early last year, adjunct N.W.A member Arabian Prince produced a novelty single for some hangers-on, J.J. Fad, as a side project: “Supersonic.” The single sold half a million copies on Dream Team Records. Every record company in the world was after the album. Eazy leveraged J.J. Fad away, licensed them to Atco, and had Dre produce the album, which also went gold, for the aptly named Ruthless Records. “It’s what we call a ghetto LBO,” N.W.A publicist Pat Charbonnet says. “Eazy’s the Gordon Gekko of Compton.”

Arabian left the group. The Priority pickup deal was signed, and Eazy recruited an old friend, Ren, to write three songs — “Radio,” “Eazy-Duz-It,” and a brilliantly funny bank-heist fantasy called “Ruthless Villain” — for a single. Covering his bets, Eazy hired KDAY DJ Greg Mack to do an intro to “Radio” a la Parliament-Funkadelic, and signed KDAY morning-jock Russ Parr’s comedy-rap act Bobby Jimmy & the Critters to Ruthless/Priority. (No ulterior motive is implied here, but the move probably didn’t hurt the record’s chances for a decent rotation.) The “Radio” 12-inch sold 140-odd thousand copies. Ren joined N.W.A, wrote much of Eazy’s album and, when Ice Cube returned last September, helped to write Straight Outta Compton.

Eazy Duz It went platinum, but was largely unremarked upon. N.W.A coined the phrase “reality rap,” which guilty white liberals find a convenient term when explaining why they like the album so much. Word of the N.W.A album was picked up by CNN and the city desk of the Herald — more as a news story (“L.A. Gangs Speak”) than as an entertainment story — and suddenly Eazy and the gang were promoted from amusing hoodlums to spokesmen for a generation. The L.A. Times found them progressive and put them on the cover of Sunday Calendar.

There were two triumphant sold-out shows at the Celebrity Theater in March; although they were sloppy, N.W.A outperformed Ice-T for the first time. The audience knew the words to the songs well enough to rap along. During “Dopeman,” Ice Cube brought a cute white girl on stage from the front row. A few seconds into the song, while band members humped against her, 2,000 people merrily pointed and chanted, “She might be your wife and it might make you sick/To come home and see her mouth on the dopeman’s dick.” Later, the mob shouted “F-Fuck the Police!” in unison. Ten minutes later, a melee broke out on center stage and the cops were called in even as Eazy strutted among the turmoil, grinning, finishing out the set. There were stabbings that night.

Most rapping used to promote the rapper’s indomitability, his invincibility: “I create; I am.” When Public Enemy has Chuck D in a prison cell, it is only so that he can break out; when an L.L. Cool J rhyme includes a policeman, he is only there for L.L. to outwit. A rapper, whose implicit statement is always “You want to be like me,” is a role model whether he sets out to be one or not. If nobody wanted to be like him, nobody would buy the record.

Many whites and blacks find N.W.A frightening; mainstream black leaders hate them because of their distorted image of the black community. They celebrate the gangster life and reinforce racist iconography. Yet if you get past the language and violence — a line like “Fuck you, bitch” serves the same purpose here it does in an Eddie Murphy routine — you’re struck by the powerlessness the first-person lyrics project: “I can fuck you up; I am.”

When a policeman appears in an N.W.A song, he’s got Ren face-down on the pavement in front of his friends. In the course of an N.W.A song, crimes are punished, women are faithless, and somebody else’s stupidity inevitably leads to retribution, which leads straight to jail for keeps. N.W.A choose not to live out the omnipotence that rap is all about .?.?. their most controversial song, “Fuck tha Police,” is the ultimate expression of hip-hop weakness in the face of police power, the sort of snarling anti-cop rant left unsaid until the black-and-white is around the corner and safely out of earshot. “Fuck tha Police” isn’t a metaphor for anything.

N.W.A call themselves “street reporters,” another phrase parroted by journalists. “We don’t tell no fiction,” Ice Cube says, “so N.W.A can’t get any harder unless the streets get harder, know what I’m saying? If somebody blows up a house and we see it, we’ll tell you about it.

“If we were all for gangs, we’d be going, ‘Yo, go out and Crip.’ We’re just telling them what the gangbanger shit is like. And what would happen. At the end of the song, you might end up in jail or dead. If you get away every time, you’d be a super hero.”

“We’d look stupid trying to be political,” Ren adds. “The street’s political enough. We’d lose all our fans. I don’t really know about Mandela and Malcolm X and people like that. It would be like Public Enemy rapping about 8 Ball. You’ve got to stay what you are from the jump.”

“Straight Outta Compton,” the title track from N.W.A’s first album, is violent even before anyone says a word, a strong backbeat overlaid by a nervous repeating snare fill that palpitates like coffee jitters, like a sick feeling in the pit of your stomach, like an itchy trigger finger. The beat is scary all by itself in this song — too intimidating to dance to, really — not an in-your-face sort of deal like Public Enemy or Big Daddy Kane, but somehow ruthless, quietly intense. Under this, a single quarter note repeats, plucked on an electric guitar, and a thick, long tone — roughly sampled tenor saxophones, it sounds like — is deliberately underblown and brought up to a sour, wavering pitch, as if on a tape machine low on batteries. The sound fabric breathes, creepily alive. Faint cries can be heard in the background on the offbeats of three and four, as on Rob Base and DJ E-Z Rock’s “It Takes Two,” although they seem less cries of passion here than distant cries for help. An AK-47 shudders and, horrified, you can sense the beauty in the sound.

The rhymes on the album are clean, aggressive and profane — tropes on the word “motherfucker” and riffs riding on hopped-up 12-guage adrenalin. Alone among rap crews, N.W.A has four equal rappers, each with a characteristic voice and a distinct writing style. Ice Cube is an angry young man with a dusky tenor flexible as a viola, an intelligent but damaged hothead likely to go off randomly; Ren is the deep-voiced enforcer, loyal, violent and thorough; Eazy is laid-back and vicious, in control, funny as hell; Dre is clever, forceful yet tentative.

The vibe, when it’s not hardcore pissed-off, is easy, merry, casual, fun, as if the guys were just cutting loose in the studio in front of a live mike, the sort of carefully scripted heavy-bottom street-corner jive Parliament-Funkadelic did so well in the ’70s. (Songs are punctuated with staticky comments from the engineer’s booth, the thwee of rewinding tape, expressions of pleasure at the unexpected in-studio appearance of Eazy-E — on Eazy’s own record. It sounds like a bunch of guys sitting around listening to a record, not making one.) A song might take its form from a call-in radio show or an interview with a probation officer.

There are precedents for this sort of thing — Starsky and Hutch, Iceberg Slim’s novels Pimp and Trick Baby, Leroy and Skillet, over-the-top blaxploitation pictures like The Mack and Dolomite — although nobody ever assumed that Redd Foxx or Rudy Ray Moore had any moral authority over the nation’s youth. Take out the cussing and it turns out the gangster crime-spree narrative of “Gangsta Gangsta” is nothing the network censors would blue-pencil from an average episode of Wiseguy. The lyrics of Satan-metal bands like Slayer are unquestionably more violent.

N.W.A’s canny self-identification as a ruthless Compton street gang, though, is close enough to blur the knife’s edge between streetwise fantasy and funky cold experience. Excruciatingly detailed accounts of a burglary, a liquor store holdup, a bank robbery or a drive-by shooting make equally uncomfortable both the people who think N.W.A might not be fronting and the people who’re sure that they are.

A prominent Crip hung up on a journalist friend when she asked him about N.W.A; he thought they were just talkers (giving gangbanging a bad name, perhaps). A local rap promoter who’s been active in L.A. hip-hop as long as it’s existed swears N.W.A are currently active gangsters, gun-crazy, slinging ’caine. (He’s almost certainly wrong, by the way.) To celebrate the Eazy E and N.W.A albums last fall, Priority threw a pre-release bash at the World, a not-very-swanky disco in the Beverly Center. The doorman, thinking N.W.A were a bunch of thugs, refused to let them into the club for their own party. Eazy, at least a foot shorter than the doorman, threw a punch. N.W.A never made it inside.

N.W.A themselves, although they insist they know gangbangers but are not themselves gangbangers, are remarkably cagy about all sorts of basic facts: age, school, girlfriends, where they live, what they did before N.W.A.

It says something about who they are that what they’re trying to hide could either be criminal records or solid B averages and high-school diplomas. “You’re not bringing up our skeletons,” Eazy says, cocking a finger. “That’s dead.”

March ’89: The day MTV banned their “Straight Outta Compton” video, N.W.A is hanging out at the Torrance recording studio that’s the seat of the Ruthless empire. They are all surly — they were counting on the video, a brutal verite gang-sweep scenario directed by Australian Rupert Wainwright, to put them over the way that Tone-Loc’s did — and upset about a Compton flare-up between the Piru Bloods and the Atlantic Drive Crips: They’ve lost friends over the weekend. Concert-volume beatbox riffs whump from specially built 18-inch playback woofers in the engineers’ booth where Dre is recording the B-side for the next single, a stripped-down jam called “Give It to Dre.” He hunches over a record on a turntable like a studio guitarist over his ax and grimly scratches in the break time and again over the beat. “Give it to Dre .?.?. G-G-Give it to Dre. G-Give it to Dre and the boy is done.” He makes a mistake and Yella rewinds the tape. “Fuck the image!” somebody yells from the next room.

A slight blonde from PBS takes notes for a possible five-minute segment on the band; Ice Cube, Eazy and Ren sprawl over easy chairs in the lobby, zombielike, doing phone interview after phone interview. “Kids want to hear about reality,” Ice Cube says again and again. “White kids don’t live in the ghetto, but they want to know what’s going on.” Ren cuts in on cue: “If you’re watching the news and Tritia Toyota says three people got killed in McDonald’s, it’s not like she’s telling you to kill them — she’s just telling you what happened.” Ice Cube stands up, stretches: “But y’all have mwa-ral authawrity,” he says, imitating the last interviewer.

“If they don’t buy our records, fuck that shit.”

He pulls a scrawled-on sheet of three-ring paper out of his pocket and walks into the studio. Yella rolls the tape, and Ice Cube starts to rap. His staccato drawl is devastating, playful, spontaneous yet on; he knows exactly which syllables to punch and which to roll; he’s comfortable and in control, although he seems to have written the rhyme only minutes before. It’s like hearing Clifford Jordan try out a new standard on tenor. It’s clear that Ice Cube would be a star rapper with any producer in the country.

In the waiting room, Ren finishes up another interview and starts talking to his buddy Laylaw about Compton. Laylaw has heard this story many times:

“I lost a lot of friends to gangbanging, man. When you been kickin’ it with somebody, and you hear they dead, you think like, ‘That was my homeboy, that was stupid.’ The night I got shot, I was in front of a friend’s house just kickin’ it. You know, we wasn’t doin’ nothing. It was one of my buddies, though, who was into gangbanging; he was into it. The Crips were over here, right? And the Pirus were over from across the boulevard; I guess they came and spotted his car, which was parked where all of us were at, like, 2 in the morning. My friend says, ‘Come on, man, let’s go watch some movies.’ All of us walking in the house, they just start blat-blat-blat-blat — shooting and shit — and I got hit. And you know, after I get shot I was like ‘Man, damn what they shoot me for? I didn’t do nothing.’ It’s all because my friend go around shooting people. I got his bullet, man, because a bullet don’t have a name on the motherfucker. Since then I haven’t wanted to be around my friend too much anymore.

“But when we put this shit out on video and on records, ain’t nobody want to see this shit. The video ain’t half of a half of what go on for real. It’s just a little sweep, no guns. MTV’s into all that crazy devil-worshipping shit .?.?. To me there’s more violence on a motherfucking cartoon than in our music. Little kid see a cartoon character with a gun, he going to want to carry a gun, right? GI Joe, all that shit. But they aren’t even playing our video on the MTV rap show.”

(“N.W.A: A Hard Act to Follow” is a reprint of May 5, 1989 L.A. Weekly cover story).

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.