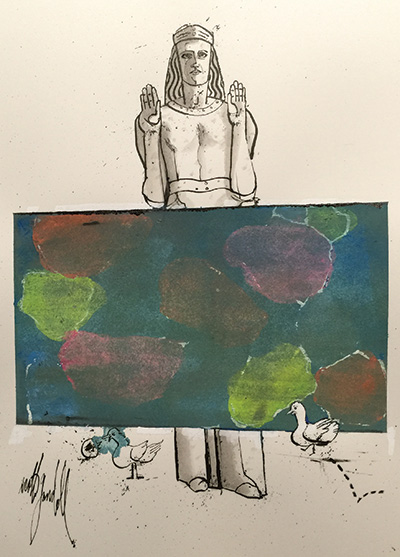

Illustrated by Scott Gandell

There wasn’t supposed to be water here. They brought it with them. They swallowed up the Earth with it and let it seep into the ground, men shoveling and heaving to make a hole, a massive bathtub to fill with water and call a lake. The water was clear then, not murky like it got to be, clear and lined with lotuses, fragrant and full, white saucers with yellow yolks. They are gone now. The water, drained. A mound of gravel rests in the middle of the lake, waiting to make a parking lot.

The statue of The Lady of the Lake still stands, tall and proud, on the tip of the peninsula overlooking the cracked dirt. Her mouth is tightly closed, as if she is holding in a secret. Her eyes are hollowed and emptied by the broken promises of others. Yellowed photographs of deceased women and children litter the cement block she stands on, smiling faces perched against candles of La Virgen de Guadalupe and wilted marigolds.

She is stuck here, just like me, stuck to this Earth. This woman encased in stone. I hunch over her feet and touch the folds on the bottom of her gown. It feels cool beneath my palms. My fingers claw at the tips of her toes; the mud from my hand smears the white stone black as I kiss her feet. My fingers poke through the holes of my dress—the tears and snags caused by fallen tree branches and shrubs, the ones that used to line the lake before they were uprooted—as I wipe the dirt away from her toes.

Before the lake was closed off, they came for her, Angelenos bearing gifts and prayers.Abuelitas with their roses and spicy mango slices, pimply-faced teenagers looking for a place to spoon, models in polka-dot bikinis and evening gowns contorting their bodies for the camera, men on their lunch breaks drinking forties, families celebrating birthdays, quinceañeras, anniversaries, and deaths.

At night, boys who wanted to be men would touch her. They came to leave their mark on her, to try and claim her as their own; ExP is sprayed across her breasts, AHTS across her hips, and LA on her back in red. The boys were covered in signs too, cryptic layers of ink that covered their faces, chests, and arms—messages of love and hate that peaked out from beneath their shirts. When they thought no one was watching, they cried at her feet and pleaded for her to pray for them, to help them.

Even now, the fence doesn’t stop them. They cut holes in the bottom of the chain-link and swiftly squeeze themselves through it or, if they’re strong enough, climb over. Their movements send ripples through the metal and, when they reach the top and jump, their momentarily airborne bodies appear weightless.

Like those boys, I beg for her help, for her forgiveness. I beg her to undo the curse placed upon me. I get down on my knees and weep. I repeat the names of my children under my breath over and over. The children I have lost because of my own selfishness. I tell her to punish me for what I have done, to fill the lake with water again and send me to the bottom of it with them, to send me someplace, anyplace but here. Please, I say, anything but this silent waiting. I clasp my hands tighter together and burrow my nails into my skin, hoping to break the flesh. I feel nothing. I collapse at her feet, waiting for guidance, waiting for a sign.

* * *

When they came in their trucks, men shouting with their helmets and drills, I watched as they slowly drained the lake, as they destroyed what they had made and nature had gotten used to.

At first, I thought they had come to rescue me, to save me from the land I was tied to. Men with purpose, I thought, men who could move mountains and lakes if they wanted to.

“Are these the children who will save me?” I asked The Lady.

She stood over me. Be patient, her eyes seemed to say.

I tried. I sat and watched the workers as they came and went. Their neon vests moved like clusters of ants as they stomped through bougainvillea bushes and tore up patches of grass, clearing the perimeter to make space for their fence. I saw the greed in their eyes as they did it, as they put their metal posts into the ground and glued them to the Earth with concrete, closing off the lake to everyone but themselves, trapping The Lady and me inside of our home.

They brought long hoses that moved across the lake’s surface like hungry snakes. They gulped down the water and pumped it into the tanks that waited on Glendale Boulevard, gallons of water that were packed up and driven down the 5, out the 710, and into the Pacific.

“Are these the children who will save me?” I asked The Lady again. “Will these men destroy my secret, my shame, and I will be set free?”

As they drained the lake, I closed my eyes and remembered them. The faces of my children as they floated in the water, their mouths open as they cried out my name, as they cried for help, begging for mercy. Their limp bodies on the water’s surface, their hollow eyes staring up at the sky. I saw the pale little faces and the round cheeks. She has your eyes, people used to say. He has his nose. They haunt me. Those empty eyes pleading for help.

I open my eyes and look out upon the dry muck. The secrets the lake has kept hidden, wrapped tightly in her soil, lay naked upon the ground, basking beneath the sun. But my secret, my shame, remains hidden deep inside me.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.