Illustrated by Santosh Oommen

“Ma!” Chhouka yelled as she burst through the doorway, her yellow-flowered socks skidding across the hardwood. “Guess what Mr. Scott asked us to do toda—“

Chhouka froze in her tracks. Her mother was hunched over the kitchen table with her face buried in her palms, her frail shoulders heaving. She was bathed in the dusky light dancing through the half-shut blinds.

Chhouka stood awkwardly at a distance from the table, at a loss for what to do next.

“Ma?” she said quietly. “Are you—are you okay?”

Ma jumped up from the table, hastily smearing away tears on her cheeks, but not before Chhouka saw them. She bustled over to the other side of the small kitchen, her back deliberately facing Chhouka.

“Yes, I’m fine,” she answered stiffly in Cambodian. “Why wouldn’t I be?”

Chhouka shifted her feet uncomfortably. She’d never had the privilege of sharing raw emotions with her mother before, and she felt as if she were intruding on an intensely personal experience which she didn’t know how to navigate. How could a sixth-grader handle the responsibility of comforting a mother in pain?

When Chhouka didn’t answer, Ma cleared her throat. “Call Ba down dinner. Now. It ready,” she said tersely, in her fragmented English.

When the three were eventually seated for their daily family dinner, it was only five in the afternoon.

Before, Chhouka never wondered why they ate supper so early and had always accepted her family’s unusual way of doing things—gathering to eat in between her parents’ busy shifts, as they each worked two jobs; their chipped, stained bowls and old bamboo chopsticks that oftentimes shed splinters in their food; their simple dinners of dry white rice and canned vegetables donated by the temple—and, if they were lucky, pork belly or duck skin.

But everything changed two months ago when Chhouka started watching a popular sitcom on television, featuring a blonde American family. At the end of each episode, they gathered around their table every night, murmured prayers that ended in Amen and not in Cambodian, and devoured a feast of pasta and burgers. With each episode, Chhouka started to feel more embarrassed and dissatisfied at every dinner with her parents, but she couldn’t pinpoint why she felt this way.

She drearily pushed her green-beans-from-a-can around with her chopsticks, pretending to not notice the stony silence burying itself in the space between her parents.

Chhouka’s mind started wandering, and she vaguely remembered what happened last night as she was going to sleep. She was just about to doze off when the familiar noises of her parents shouting rose from the next room, shrill voices flinging harsh words at each other. Their bellows poured through the thin walls of their tiny apartment and mixed in with the sounds of the city, engulfing Chhouka in a dreadful symphony she desperately wanted escape from. She attempted to drown out the thunderous shouts of Ma and Ba and pretended as if she didn’t hear the two gunshots that emitted somewhere in her neighborhood.

She was nearly used to this nighttime routine—but not entirely. Somewhere in the back of her mind, she believed that one day, things would change.

Chhouka eventually dozed off, and she had nice, happy American parents. She came home to parents who spoke to each other warmly and held hands in public and who proudly declared their love for one another. Those three words had never sounded so powerful.

When Chhouka woke up that morning in a fury of hot sweat, she attempted to recall the last time Ma and Ba engaged in physical affection with one another—or even with Chhouka—but she couldn’t remember. In fact, she realized she’d never heard the word “love” in their vocabularies before.

As Chhouka sat at the table, she was more aware than ever of the tense silence blooming between her parents. When they dutifully said their Khmer prayers and raised their plates to eye level, as a sign of respect to the Buddhas, Chhouka noticed the physical distance between their bodies. As they started eating, all she heard was the clinking of rice bowls that were emptying much too quickly, and hot anger began to bloom into Chhouka’s cheeks.

“Chhouka, why you not eating your food,” Ba snapped irritably in English, interrupting her train of thought.

“Because it’s the same every night, and I’m just sick of it,” Chhouka muttered back, surprising herself. She normally never talked back to her parents, but her unease made her unusually defiant.

Ma slammed her chopsticks on the table. “What you say, Chhouka?” she hissed, her eyes narrowing.

Oh no, Chhouka thought frantically. Maybe I shouldn’t have said that. But as she met her mother’s eyes, the same shade of deep brown as hers—so dark that they were almost a glassy ebony reflecting everything before it—she felt a creeping sense of rebellion that was simultaneously scary and exciting. For a moment, Chhouka was conflicted between fighting the agitation and allowing it to overtake her. She swallowed the dryness in her throat.

“I said, Ma, that it’s the same thing every night. Why can’t we have normal American meals, like spaghetti and meatballs? Why do we always eat the same rice every night?” Her voice quivered.

The aghast expressions on Ma’s and Ba’s face instantly confirmed Chhouka had made a grave mistake. In the brief moment of silence, both of them shared the same look of vulnerability. Suddenly, Ba’s weathered face looked much older, his wrinkles longer and deeper, and Ma’s sunspots seemed to darken.

“Chhouka, you already know temple give us food; we take what we get,” Ba said quietly. He suddenly looked very small to Chhouka; a man who stood at six-foot-two seemed to deflate before her very eyes. She felt the deep sense of humiliation in his voice; not just from their family’s circumstances, but from disappointment in her behavior.

“In Cambodia, during the genocide, we had no food,” Ma said in Cambodian, with great difficulty. “The government tried to starve us out. My own Ma found bark and dirt for my six siblings and I to eat. If we were lucky, we were able to eat from dirty wrappers or old leaves, and we pretended like we were in our kitchen, back in our own house. We had no plates, or chopsticks or cups.”

Chhouka swallowed harder, tears blurring her vision. She hated how they always played this card—Khmer Rouge this and Khmer Rouge that. It was the classic guilt trip they pulled on her every single time. She could never win an argument. It wasn’t fair—it just wasn’t fair! The nice American families on television never had to struggle for food or money—everything came so easily to them.

Despite the toxic feelings of indignation brewing inside her, Chhouka knew she had far overstepped her boundaries, so she quickly changed the subject.

“Anyway, today, Mr. Scott announced the yearly class trip, and it’s to Washington D.C., and it’s only fourhundreddollars, and we might even get to meet the Presi—”

”Four hundred dollar?” Ba sputtered in English. He was nearly in laughter at the ridiculousness of Chhouka’s request. “Chhouka, you must dreaming!”

“No, Ba, I’m not joking,” she said firmly. “I really, really want to go. It’s the sixth graders’ last trip before we graduate elementary school! It’s our farewell trip, Ba.”

“That more than I make in one month from my gardening job! Ha!”

“And in Cambodia, we no got… trips!” Ma scoffed. “Student went school just for grade, to work hard and be smart. Your grade not even all A! You think that good enough to go to the capital, for the Pres-ee-dent? Even I know what capital of United States of America is like!”

“Well, maybe I don’t get good grades because you and Ba are never there to help me with homework! All my American friends get lots of help from their parents, whenever they want!” Chhouka shot back.

“You know that Ma and I are working two jobs each. Of course we do not have time to privately tutor you, Chhouka! And do not forget, you are not American! You are Khmer, and you should be damn proud of it!” Ba roared back in Cambodian.

“Just—just STOP talking about Cambodia!” Chhouka stood up from her seat abruptly, bringing her small fists to the table. “Oh, you guys had to walk for miles with no shoes and went hungry—yes, I know, you’ve told me about a million times! I get it, okay! But I am not Cambodian—I am American! Do you know what Amy and her friends called me at recess today? They pushed me on the floor and said, ‘Chhouka sounds like choke, which means death! That means Chhouka’s going to die early!’ Why couldn’t you just give me a normal American name? Chhouka, what a stupid name! What were you guys even thinking?” Her chin was quivering as she fought to hold back the burning tears, but her temper was beyond the danger zone now.

“You would have been a disgrace in Cambodia,” Ma said quietly in Khmer. “An utter disgrace.”

Chhouka flinched, recoiling from the sting of Ma’s words, but she was exhausted from hearing the repetitive story of their great escape from the evils of Cambodia, over and over and over again!

She knew the tale of their journey word-for-word: her father’s family, the Khats, was a wealthy clan of nobles before the Khmer Rouge, Cambodia’s Communist Party, arrived. When they took over the regime, the Khats became a target. They were forced out of their homes into the rural areas for agricultural labor, and it was in these labor camps that Ba lost his whole family. One by one, each of his relatives was tortured and killed. After his parents were both murdered, Ba finally made the decision to escape with Ma to Thailand, where they lived in a migrant camp for two years. They eventually saved up enough money to sail on a cramped cargo ship to California, where they settled in an extremely poor, but tight-knit Cambodian community.

Chhouka has heard this story countless times, and in the past, she used to feel great sorrow for her parents’ suffering, but the retellings lessened its effect.

She was six when her parents taught her the meaning behind their family name, Khat, which was Cambodian for “triumphant or courageous.” Six-year-old Chhouka subsequently asked,

“Are we named Khat because we are very brave?”

Ba only chuckled in response, but Chhouka persisted.

“Ba, don’t you think you and Ma were brave, for making it out of the genocide alive?”

Ba suddenly paused, the shallow lines on his face frozen. He inhaled sharply.

“Do you think we were braver than the ones who didn’t make it?” he asked softly.

The sorrow on Ba’s face during that conversation, five years ago, was the same expression he wore on his face now as he stared down at his daughter.

Ma, on the other hand, was seething with rage. “Chhouka, come, now,” she said through gritted teeth. Her voice was edged with dangerous fury. She stomped out the door, not even looking back to see if Chhouka followed—but of course she did, because by now, she was regretting all the words that had flown out of her mouth. Shame quickly settled in and stifled the words that were threatening to burst out of her lips just moments earlier.

Chhouka knew the trail they were walking on: it was a well-beaten dirt path towards the local temple. She had walked this road with her parents countless times to attend the weekly services, for they didn’t own a car. She followed her mother’s rapid footsteps through the scattered, worn-down apartments of their neighborhood, attempting to settle the queasiness in her stomach.

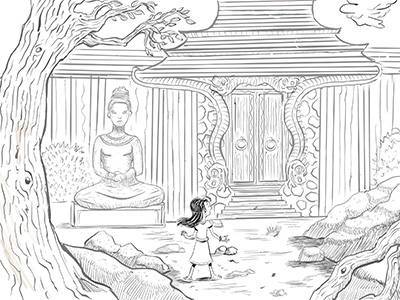

They soon approached the Buddhist monastery, Serenity Temple, and despite her unhappiness, Chhouka looked up at it with the same awe that washed over her every time she stood before the building. No number of visitations would ever erode the sense of wonder she held as she stared up at the spellbinding architecture. On the golden roof sat four elegant dragons, the Guardians of the Four Directions. Their scaly emerald bodies curled around the building, meeting at the entryway and forming the four borders of the doorway.

They passed by a room with a row of enormous statues of deities, and Chhouka made a small bow to the carving of Maitreya Buddha, positioned at the entrance. She’d always felt quite fond of the fat, joyful Laughing Buddha, who had an eternal broad smile and cheerful eyes, with a big belly protruding below. Ironically, he held an empty rice bowl, on which was carved, “To be hollow is to be filled.” When Chhouka first saw that quote at the age of four, she didn’t understand what it meant but decided she liked it anyway. Ma explained to her that the bowl wasn’t filled with food because Maitreya was full from happiness and divinity, but Chhouka was far too young to understand what that really meant.

Chhouka wondered what they were doing in the temple. Was Ma so horrified by her daughter’s misbehavior that she wanted to pray away her bad deeds? Would burning incense really be able to change her thoughts? She hoped that’s not what they came here for. She couldn’t shake off the discomfort that crawled over her spine every time she entered Serenity Temple.

Despite spending a fraction of her life here, Chhouka never truly felt at home in the temple, the way its monks and other visitors seemed to. Their expressions always took on a peaceful look as soon as they stepped through its doors, as if they were utterly unaware of the external world as soon as they were within the walls of the great monastery. They seemed to shed their troubles at the doorway, like an old coat they didn’t care enough to keep wearing.

Ma and Ba were like that. They would bicker up to the very last step of the temple, and right from the very first marble tile, their lips would relax, and their faces would soften. They spoke more affectionately, they smiled at the monks, and they even occasionally held Chhouka’s hand as they guided her through the labyrinth of rooms. She always cherished the moments when her small hand would be enclosed in the large, safe palms of her parents. However, their happy, trance-like state would only last the duration of the visit, because as soon as they exited into reality, they would resume into bitterness and resentment. That’s why Chhouka detested visiting Serenity Temple—because it only gave serenity to those who remained inside its confines but not when they left to return to their daily lives.

Chhouka always felt so small amidst the towering golden gods, as if she were an insignificant speck of dust amidst a tornado of matter. She knew religion was supposed to make one feel important, but how could she ever matter? And though she admired the intricately carved statue, she wasn’t sure if she could feel the true presence of the Buddhas; she just never felt a divine connection with them, like the scriptures claimed she should. The omnipotence of the deities scared her; for their all-powerfulness felt like a threat to her and her small family. Besides, if the Buddhas could really do anything, why couldn’t they make Ma and Ba love each other again, or give the Khats more money so they’d have to stop working four jobs to support the three of them?

Chhouka stood staring at the tiny pond that was covered with a thick layer of dirt and silt. She was utterly perplexed, until she saw a beautiful sight.

But there, floating in the brown water, was a single pink lotus flower. Its rosy petals sprouted out from a golden stamen, and the velvet skin was tipped with crimson stains. As she gazed at the flower growing in such an unlikely place, her mother walked up behind her and began to speak.

“I was eight months pregnant with you when we escaped,” Ma said in Khmer. “We wanted you to have a safe and promising future, away from the horrors that we had to face as a young married couple. That was no future. That was a living hell.”

“You were pregnant with me in the migrant camp?” Chhouka whipped around, surprised. “You and Ba never told me that.”

“My little Chhouka, we spared you many details,” Ma said with melancholy in her eyes. “There are many things Ba and I have not told you about our long journey. But I am telling you now, because you have many questions we have not been able to answer in the past. But you are of age, and you deserve to know these stories. These are not just our stories anymore, for they are a part of your birth into this world. They are a part of you, Chhouka.

For three weeks during our attempted escape, Ba and I were separated. He was captured by local villagers who wanted to sell him back to the Communist Party in exchange for more food, and I had to hide in the fields during that time, waiting and waiting and waiting. I didn’t know whether your Ba would make it out alive, and I had no way of knowing what was happening to him within that village. I was so frightened, Chhouka. The longer I waited, the more risk I had of going into labor, or getting caught and possibly executed. And though I prayed constantly, I was starting to lose hope. I would have never even thought of abandoning Ba if you weren’t in my womb, for the thought of risking your life shattered my heart.

I was nearly ready to give up and return to my family in the labor camp, where I could safely give birth to you. One night, as I laid hidden in the rice paddies, I saw the whole world aglow with the light of the moon. It was like nothing I’d ever seen before. The shimmering air danced in the breeze, and everything was kissed with moon rays, gleaming white and silver. I closed my eyes and meditated, and I felt the presence of the Buddhas right beside me. I could feel the warmth of their spirits against mine.”

Ma’s eyes shone in a way Chhouka had never seen before. Her eyes were far away, engulfed in a tale that occurred when Chhouka’s life was just beginning.

“I whispered to the Buddhas, ‘Please, if I am destined to stay and wait for my beloved husband so we may escape together, give me a sign.’ When I opened my eyes, right there in the mud before me, a lotus bud appeared out of nowhere. It started blooming slowly before my eyes, unfolding silky petal by silky petal, until it grew into the most magnificent lotus I had ever laid my eyes on. I could feel the warmth it radiated, and I was immersed in the lovely pink air, and for a moment, everything was golden and magical.” Ma almost seemed to radiate as she dreamily relayed this story.

“Did you take it, Ma, to keep with you?” Chhouka whispered, her eyes wide.

“No, Chhouka. You see, beautiful things created by the divine have to be released, or they will die in the hands of the greedy human touch. I left it there in those muddy waters where I knew it could live out the rest of its lifespan. Everything in this world has a life. Even plants. As I walked away, I knew two things, and two things only: one, that I needed to wait not much longer for your Ba’s release, and two, that your name should be Chhouka.”

“Why did you name me Chhouka? What does my name have to do with the story?”

“Chhouka, my darling, is Khmer for ‘lotus’,” Ma replied, her eyes fierce and sparkling.

“Because even though you originate from the muddy waters of destroyed Cambodia and our broken family tree, we hoped you’d blossom into something unexpected and extraordinary, never letting your external circumstances define your growth, my dear Chhouka.” Ma’s fingers found Chhouka’s hands, and she gently caressed them.

“No matter how long your petals grow or how lovely you glow, your roots will forever be intertwined with the muddy waters that your Ba and I escaped from to secure our family’s future. You are eternally rooted to the tragic Cambodia that birthed Ba and I. We are your roots, your stem and leaves, but it is up to you how to grow into your own petals, my little lotus flower.”

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.