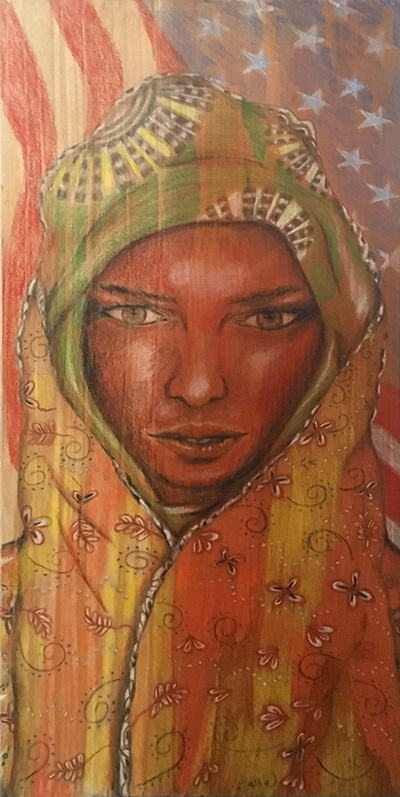

Illustrated by Jen Swain

I look like my mother, which means, as the masjid aunties are quick to remind me, that I will never be as beautiful.

“You look more and more like your mother everyday,” they always begin, these third world aunties with their overly familiar ways. “But your nose isn’t quite as long, and you’re much, much too thin.”

This is America, I want to tell them. You can’t just tell people what you think about their appearance. But I know that I could never bring myself to say this to the women who were witness to the slow unfolding of my girlhood. Besides, here in the masjid there is no America. It is unincorporated land: a liminal space between the lives we’ve left behind and the ones we have attempted to cobble together.

We are immigrant women, refugee women, converts, and born-agains. Women who, when they dream, dream of the desert plains they’ve left behind. Imagine it before the war, or after, after the blood has dried, the dictators have been toppled, and military leaders no longer swarm the streets in ravenous packs, leering and groping underage girls on their way to school. Long after the dead have been buried, prayed over, and forgiven.

How do you mourn the death of a country that you’ve only ever seen in a dream? How do you grieve the things you’ve lost when they are innumerable? These are questions with no answers: questions that burn like pillars in the far off horizon.

When mama takes me home with her for the first time in 2012, I don’t know what it is that I am looking for. I don’t know what it is that she has returned to find. We arrive only to discover that the old neighbors are long gone, and no one who’s replaced them knows our names.

Ayeeyo shows me around the city, but she is shy, as if the country’s failures are her own. She is embarrassed by the men on donkeys hustling water; she is embarrassed by the piles of trash that stink in the blazing heat of a Hargeisa afternoon.

All mama ever wanted from America was a house of her own—something to anchor her to this new country. She couldn’t afford one, not until much later, but in the early years of her un-homing it was here, with other women, in the House of God.

This is why I indulge the masjid aunties and their wildly invasive questions. I assure them that yes, I will get married soon, and yes, of course they will all be invited to the wedding.

Besides, maybe I will be a masjid aunty someday: a woman who force feeds her guests in a dramatic display of love; who wears orange and green and yellow at the same time; who talks too much shit; who takes no shit; who gets married too young and resents her husband; who tries to raise good boys but fails embarrassingly; who prays for daughters who rub rosewater behind their ears. A woman who remembers the droughts the ancestors survived, who still, after all this time and all this distance, dreams of rain.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.