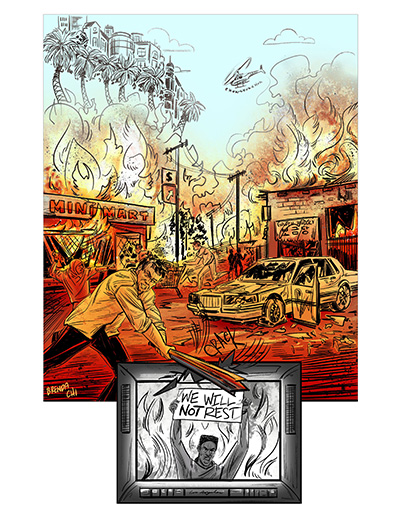

Illustrated by Brenda Choi

A South African friend of mine was visiting Los Angeles a week before the city immolated on the fires of neglect and rage. He’d lived here while attending the then Graduate School of Urban Planning at UCLA and had returned to Johannesburg to head the urban policy section of the Urban Foundation—a liberal-to-left think tank plotting economic strategies and tactics for a new South Africa.

Over some Cuban food and a few beers we kicked it as to how in the fifteen months since he’d last seen LA, the city seemed to be fraying more. Not from the edges but from the center outwards. He also reflected that JoBurg was not so different than the city of lost angels: Whites ensconced behind high walls shrouded in webs of electronic security, a growing chasm between those who want and can get and those who go wanting, an exploited immigrant labor force, and recession and crime at an all-time high.

Yet like the promise of a shiny mansion on a distant hill, the allure of a coming economic boom seduces both cities: JoBurg positioning itself to become one of the centers of finance capital, which will infuse the whole of southern Africa; and Los Angeles waiting to reap the rewards as the center of Pacific Rim finance. The city is building huge skyscrapers and massive office complexes on spec—allowing for numerous vacancies against future returns—while in some areas of town African American and Latino males suffer double-digit unemployment.

We talked of those economic matters, films we’d seen, books we wanted to write, and of course the pending verdict in the trial of the four cops who beat Rodney King. My friend, who is white, left Los Angeles a day before The Verdict and the whirlwind it unleashed. He and I made commitments to keep in touch as the uncertainties of our respective hometowns played themselves out.

Wednesday afternoon, the 29th of April, all of LA, and certainly other parts of the country, awaited the jury’s decision in the courtroom located in east Ventura County. In particular this was the bucolic Simi Valley, site of the Ronald Reagan Library.

I hadn’t been that anxious about a news report since I was in high school and couldn’t concentrate on homework and kept turning on the TV to see who’d won the first Ali-Frazier fight. But this outcome would have a far greater impact than the arena in Madison Square Garden.

This arena of Simi, thirty-seven-odd miles to the north and west of Los Angeles, was, and is, more than just another bedroom community begun by white flighters. It is a community, like Mission Hills, Manhattan Beach (Shaq, who lives there notwithstanding), or Newhall, where the cops, as civilians, interact with people in the supermarket, the bowling alley, and on front lawns. Not like the inner city, where young black and Latino men more than likely deal with cops who prone them across the police cruiser on Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard.

And so a few minutes after three that afternoon, the radio played the measured tones of the sixty-five-year-old forewoman who said that the jury had found the four cops innocent of all criminal charges, save for a secondary count against Officer Laurence M. Powell (the man who struck Rodney King the most times) for abuse under color of authority. The jury was hung only on this count. Post verdict, and in the wake of the massive reaction to it, the then LA District Attorney Gil Garcetti requested a retrial of Powell on this charge. But that afternoon, relatives and supporters of the cops celebrated in the courtroom while black folks throughout LA watched their televisions like Regis just pimp-slapped a contestant for messing up on “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?”

Sitting in my office at that time of the Liberty Hill Foundation (a progressive funder of grassroots organizations in Santa Monica, California), I wondered abstractly if the work of Reverend Cecil Murray, Congresswoman Maxine Waters, City Councilman Mark Ridley-Thomas, and others would go for naught. Since the previous Thursday, when the jury sequestered itself, these community leaders had been putting the word out that people had to be cool no matter what decision came down. There would be organized rallies and speak outs for the populace to vent their frustration. But the acquittal came a week and a half after an appellate court upheld the ruling of Judge Joyce Karlin in the Soon Ja Du case. Mrs. Du was a Korean storeowner convicted by an LA jury of second-degree murder in the death of black teenager Latasha Harlins. Karlin gave Du five years probation rather than the sixteen years maximum in prison others had received under similar convictions. The judge said Mrs. Du going to jail wouldn’t serve justice.

And so unanswered anger and blind fury collided at the intersections of Florence and Normandie in South Central. By dusk of the 29th, rioting and firebombing and looting had jumped off. Like Watts in ’65 when I was a kid, you could watch the action on TV. Unlike Watts in ’65, where shit was confined to a specific area, the anarchy spread from South Central to Koreatown, to Pico-Union, the edges of Silver Lake, Mid-City, and on into Compton, Long Beach, Pasadena, Inglewood, and even the gilded confines of Beverly Hills. Not only could you see it live and in color but you were part of the action too.

Yet on Thursday morning we thought the worst might be over—psychologically tricking ourselves into thinking that one night’s blowout would equal years of injustice. I went to work but my wife wisely decided to keep our, at the time, small children home from their preschool. Sure enough, Thursday afternoon the descent into the “riddle of violence” as African liberator Kenneth Kaunda phrased it, began again.

I rushed home midday from the office to find my neighborhood of Mid-City poised to go under the knife. The family gathered at a friend’s second-story duplex with others, feeling as though we were in a nameless land experiencing an ill-conceived coup. People were clamoring in the streets, darting here and there as gunshots whined through the air, cars slammed into each other and buildings, sirens screamed, and police and news helicopters swarmed about pyres of flame like giant mechanical moths. Shit was happening all around, the neighborhoods were a torrent of rip and run, yet all you could do was watch out your window—unsure of who was in charge and who wanted to be.

Stores not five blocks from us blazed red and grey into the darkening sky as the local Vons at Pico and Fairfax was looted. Three middle-aged women, one with a pistol in her apron pocket, stopped a roving band of gangbangers from torching the Texaco station at the corner of our friend’s duplex on Ogden. When night arrived, my wife Gilda drove our children Miles and Chelsea out to another friend’s house in Van Nuys in the Valley for relative safety. But being the proud petty bourgeoisie homeowner, I decided to stay at our crib so it wouldn’t be empty.

So on a small table next to the live drama on my TV set rested my loaded Smith & Wesson .357 Magnum and a half-pint of courage-in-a bottle Jack Daniels—a volatile combination in the best of circumstances.

Well, the house didn’t burn down nor did anybody, fortunately, try to bust a cap in my dome. But two personal things happened to me as a direct result of the civil unrest. It turned out our kids were incubating chicken pox because at the time it was going around their preschool and you’re supposed to let them get it to develop the immunity. But in my then thirty-plus years I’d never had the disease and subsequently got it ’cause of that Thursday afternoon being cooped up with them in our friend’s apartment. And my dad Dikes, who was alive then and seventy nine, had also never had chicken pox and subsequently got it from me. (He was living with us but in Kansas City visiting relatives when the riot erupted.) We were both miserable.

And that summer of ’92, I started to write my second book, which would become the mystery novel Violent Spring. I’d already written a previously unpublished book with the main characters—donut shop-owning private eye Ivan Monk, Superior Court Judge Jill Kodama, retired LAPD cop Dexter Grant, et al.—but knew using the backdrop of the siege and its aftermath as it shook out racially and politically would be a compelling story. Ten years later, I’m still writing about Monk’s travails and other stuff. And Los Angeles is still the sexy beast you can’t help but look in the eye now and then and write about.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.