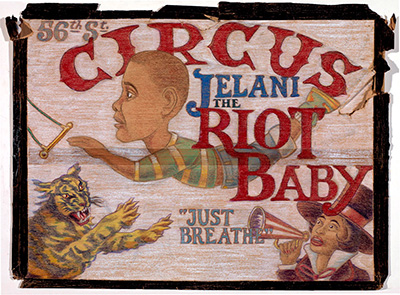

Illustrated by J. Michael Walker

Ten years ago, in the wake of the Rodney King verdicts, American society ruptured in South Central Los Angeles, resulting in the worst riots in our nation’s modern history. Ten years later, the people are still poor, there’s not enough work, and the gang violence is bad and getting worse. One other thing hasn’t changed in South Central: Little boys still grow up there. This is the story of South Central since the riots. This is the life story of Jelani Stewart, who came into this world as his city burned.

The black circus is dark and smoky and magic. And it is loud and it is black. The ringleader, Casual Cal, is black, and he’s got a black midget sidekick, and the trapeze artist is black and the guy on stilts is black and the guy who vaults thirty feet high and flips and lands on a tiny chair perched in the air is black and the magician is black and the showgirl he makes vanish and who reappears in the tiger cage is black. The audience is black, too, and at the moment, to a person, all two thousand are going completely nuts, especially Jelani Stewart, who is not quite ten years old.

Look at this boy, Jelani. He’s about to have a heart attack, y’all! He screams, No! No! No! as the girl contortionist from Africa bends over backward, curving her spine back, back, back until her perfect brown face is between her thighs and she is smiling up into the audience and rolling her eyes. Jelani grabs his cousin Kiana’s hand. Oh, my gosh!

Casual Cal pumps the crowd. “I say, Big Top, you say…”

“Circus!” Jelani shouts, leaning his head back, staring into the heavens of the circus tent. It’s like it’s not real! A family is up there on the high wire riding bicycles without nets. The deejay is spinning, and it is loud! I’m a sucker for cornrows and manicured toes…. Mommy… what’s poppin’ tonight?

Jelani’s been waiting all year for the UniverSoul Circus to come back to Los Angeles. For one thing, he gets to eat cotton candy and nobody says a thing about cavities. For another thing, all of the people who matter the most are here. There’s LaTonya, his mom, who loves him beyond words; Nana and Paw-Paw, who let him play on their computer at home; his seventy-five-year-old great-grandmother, Elouise, who raised seven kids in Watts and South Central; his auntie LaTrice and his uncle Tommy, who works at the airport; and his other cousins Tarik, Karlie, Karol, and Tommy Jr. The big-top tent is up across from a cemetery in the parking lot of the Hollywood Park racetrack. Paw-Paw sprung for ringside seats at $18.50 a pop.

Paw-Paw has a round, bearded face, short dreadlocks springing off his head, wire-rim glasses, and an earring. His name is Cornelius Reffegee, and he’s LaTonya’s stepdad. He is forty-nine years old and has been married to Pat, LaTonya’s mom, for fifteen years.

“Soul Train time!” Casual Cal announces. “I need volunteers over thirty!” Before Jelani can sing, “We’re gonna get funky, funky, funky!” Nana—who is old, y’all, she’s fifty one!—is center ring, shaking her booty in a Soul Train line. The whole family is up, stomping their feet, chanting, “Go, Pat, go! Go, Pat, go!”

Jelani’s never seen Nana onstage before, but this is the circus, and all things are possible. He looks over and sees his mom howling with laughter, tears rolling down her cheeks. Three elephants gallop into the ring, and one stops short. Jelani pokes Kiana in the ribs. Look, he’s taking a poop. The elephant wraps its trunk around the waist of a pretty girl in glittering tights and picks her up. Look, he’s got her legs and stomach inside his mouth.

What if he bites her?

He don’t got no teeth!

A light-skinned acrobat scampers onto the high wire. “Brother looks like a half glass of milk,” purrs Casual Cal, who is really on now. “I want all the large-sized women to stand up and let us see you,” he hollers. “We’re proud of you sexy ladies. And young men, pull your pants up! Nobody wants to see your underpants!”

Outside it’s bright California sunlight, but inside the big top there’s a chalky smell in the air from the smoke machines, and the colored lights are spinning, and everything just glows. Jelani was born just up the street from here, and he and his mom live a few miles east, in the heart of South Central Los Angeles, just past the intersection of Florence and Normandie. And that’s what this story is all about, Jelani being born. Because the boy’s about to turn ten, and y’all, what a ten years it’s been! Because people sometimes tell him that something weird was happening when he was in his mom’s stomach, waiting to come out, and when he was little, his Nana used to call him Riot Baby. Because he was born in fire. But he doesn’t really know much about that. What does he know? “I never ever want the circus to ever ever end!” he says. Casual Cal is worked up, too. “A man has to want to change!” he shouts in benediction. He is drenched in sweat and gleams in the purple air. “Never conceive in your mind to do anything evil to another human being.”

April 29, 1992, evening, and LaTonya Potts, aged twenty five, is in labor in Centinela Hospital in Inglewood, squinting up at the TV between contractions. An angry crowd is shouting and beating people on the TV and somebody says that you can smell smoke in the hospital and LaTonya wants her mother, who is there trying to help, to just back off. The nurse has been saying Any time now for five hours. And now, smoke and fire.

The pain is worse than anything LaTonya’s ever felt. Can somebody just turn the damn TV off? She tells herself she’ll make good choices from this point on. She just wants the baby to be born, soon, and naturally. No getting cut open. She knows it’s a boy from the ultrasound but has kept this a secret, even from her mother.

Her family has begun to drive in from all over South Central. She hasn’t seen the baby’s father, Daryl, in six months. She hadn’t trusted that man and hadn’t meant to get pregnant, and she’s only going to stay with people she trusts from now on, period.

Not far away, a man LaTonya has not yet met, Bo Noble, thirty one and still on parole from a drug conviction, is racing his gray Cadillac toward Florence and Normandie. He’s been watching the verdicts on television, and then the images, live from a news chopper, of a mob looting Tom’s Liquor at the corner there. Bo picks up his gun, chambers a bullet, clicks the safety on, and tells his homegirls: “I’m gonna get me some.”

As he approaches the intersection, a Latino couple with an infant is attacked in their car. Helicopters fly overhead, broadcasting live. Anyone who is not black, and even some light-skinned blacks who are unlucky enough to enter the intersection, are pulled from their cars by the mob and beaten to a pulp on live television.

LaTonya recognizes the intersection on the TV. Florence and Normandie is only a couple blocks from where she grew up. The contractions pound. This baby is big. A white man is being dragged out of a truck and beaten. Reginald Denny, hauling twenty-seven tons of sand in his rig to an Inglewood cement-mixing plant, had rolled into the intersection of Florence and Normandie at 6:46 P.M. He was listening to an all-music country station and didn’t hear news of the Rodney King verdict, but something is going on up ahead of him. Rocks and bottles fly past. As Denny slows, rocks and chunks of concrete smash his windshield, his doors are yanked open, and he is pulled from the cab. He is knocked to the ground and beaten in the head with a hammer; when he tries to move, another man crushes his skull with something that looks like a fire extinguisher. Mommy, please turn off that damn TV! Oh my baby, oh my baby.

Bo parks his car off Normandie and pushes through the crowd. The corner is Eight Trey Gangster territory. It feels like a party. Bottles of Olde English 800, looted from the liquor store, are being passed around. A gantlet has formed, and guys with baseball bats are smashing all the car windows. Bo knows some of these guys from his days living in the neighborhood. There’s Football Williams! He and Bo are both Crips, though from different sets, and they smoked a little weed together when Bo was living a few blocks from here with an old girlfriend. Football was always a big guy, and there used to be talk that the pros might be interested. Now Football grabs something that looks to Bo like a cinder block and smashes a white guy in the head. There is no sign of the police.

An hour ago, the police field commander for the 77th Street Division ordered his thirty officers in the area to retreat. “I want everybody out of here!” he shouted into his radio. “Florence and Normandie. Everybody get out! Now!” When two officers in a lone squad car return to rescue a Korean woman who has been beaten unconscious in her car, the officers are pelted with rocks and bricks and almost can’t escape. The crowd chants, “It’s Uzi time!”

At 6:30 P.M., as the worst riots of the century are developing in his city, Daryl Gates, the Los Angeles police chief, leaves headquarters to attend a fundraiser in Brentwood. The city has known since early afternoon that the verdicts would be delivered, but Gates did not put his department on tactical alert, and a dozen of his captains are out of town at a training seminar. Gates and Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley haven’t spoken in more than a year. After the field commander for the 77th Street Division orders his officers to withdraw from Florence and Normandie, they retreat to a command center thirty blocks from where Reginald Denny lies. During the next few hours, the police lose the city. Pawnshops that stock weapons are looted, putting thousands more guns on the street.

LaTonya’s family is being told that no one should leave the hospital. Mayor Bradley imposes a citywide dusk-to-dawn curfew. Cornelius, Pat, and the rest of the family will sleep in the waiting room.

Once the sun sets, looting and burning and killing begin in earnest. Bo kicks in store windows, grabbing what he can. Sunday Mays, who is thirty and has been in the gang life since she was twelve, rides shotgun in the Cadillac. Sunday grew up slashing and shooting, but she also loves Barbra Streisand, and she’s singing “I Want Everything” from A Star Is Born as they ride. She and Bo feel the lawlessness like a drug, and it’s euphoric. Children ride stolen bicycles; women lug bags of shoes and toilet paper. Whole families. Retribution, baby, Bo says. Payback time. Liquor stores, corner groceries, and fast-food restaurants are torched. A new fire is reported every four minutes. Firefighters are shot at and can’t put the fires out.

Bo holds his fist out the window of his Cadillac. Ash falls like snow. Fire on every corner. A laundromat is lit, now a fish market, crowds moving from building to building with torches. The Kmart and the Sav-on are looted and the Newberry’s burned down. Korean shop owners, armed with shotguns, are on rooftops. Bo jacks a woman at a gas station, steals her wallet. Some Mexicans put a chain around a cash machine and pull it down the street, sparks trailing behind.

It pisses Bo off that Latinos have joined in the looting. “Rodney King wasn’t no Mexican,” Bo says as he puts a pistol to a guy’s head and steals his wallet.

Bo and Sunday bring in their first haul. When Sunday’s landlord asks her where she got all the TVs and boxes of shoes and electronic equipment that she’s carrying up her stairs, she answers: “I’m a black business owner. I’m just trying to protect my stuff.” Bo fills his bathtub with meat, stacks his bedroom with TVs and VCRs and liquor. Open season. Once in a lifetime, Bo says. He’s dreamed of something like this since he was a boy back in Ohio.

LaTonya’s baby doesn’t come all night, as if he knows.

In the morning, the second day of the riots, the doctor breaks LaTonya’s water, but it doesn’t help. Nobody told her it would hurt this much. The doctor drips Pitocin into her vein, and the contractions come with more force now, but the baby is not moving. Then he takes what looks like a pair of spoons, and he reaches inside with them and tries to pull the baby out, but nothing works.

Bo can’t believe there are no police in the streets, and it’s late afternoon by the time the National Guard shows up (having had what the governor calls an “ammunition problem”: their bullets had failed to arrive). The looters—black, white, Latino—are swarming the stores with a crazy sense of exhilaration. Gang members and mothers with children. At 4:00 P.M., the first national guardsmen take up position at Martin Luther King and Vermont and other hot spots, armed with M16s, but it’s easy for Bo to avoid them. The looting spreads toward Westwood, up Hollywood Boulevard. An eighteen-year-old Korean is killed trying to protect a pizza parlor.

“Let’s go to Beverly Hills,” Bo tells Sunday. “Shit, yeah, we fixing to bust into Tiffany’s, get us the good stuff.”

But Beverly Hills is one of the only neighborhoods protected by police in riot gear. Bo wants to pull out his pistol, but Sunday says it isn’t going to help against that heat, and they turn around.

The riot spreads throughout Los Angeles County and up into the Valley. The TV shows a department store with no police around, and looters show up five minutes later. The city is burning. There are no cops. People come up in taxicabs, keep the meter running, grab VCRs. Police cars are turned over and set afire in the street. Flights can’t leave LAX because of the smoke.

As evening falls again on the city, LaTonya, after thirty two hours of labor, asks for a C-section. Get this baby outta me, please. At 5:49 P.M., while the city burns outside and the sirens wail and gunshot victims, the dead and the dying, are being treated in the emergency room downstairs, LaTonya is cut open and the boy is taken out. He weighs eight pounds ten ounces. He is footprinted and cleaned and brought back to his mother’s arms.

As LaTonya takes the baby to her breast, in a speech announcing that thirty-five hundred federal troops have been dispatched to Los Angeles, President Bush vows to use “whatever force is necessary to restore order.” She names the baby Jelani, from a book of African names. It means mighty and strong. She talks to him all that night. “Now I understand why you didn’t want to come out,” she says. “When you get older, you’re going to hear people talk about this day.”

Making his way through the roadblocks and the fires, Jelani’s father, Daryl Stewart, arrives the next day. Cornelius meets Daryl at the door. “Don’t you go in there unless you plan to stay with her.” Daryl shoulders his way past him. He says it is the happiest day of his life and he wants to make things work. He’s gotten himself a job, and can’t they try again? LaTonya wants her son to have a father, but for now she wants to stay with her family. On Monday, the curfew is lifted, and the city returns to work and school. Returning home from the hospital, most everything she sees out her window has been burned down. Plywood is being nailed up. Folks are sweeping. Fifty four people are dead, making this the most violent urban uprising in modern American history. Twenty-three hundred wounded. Twelve thousand arrested. One thousand fires. Eight hundred businesses burned down.

LaTonya and Jelani stay with Cornelius and Pat for six months, and then they move into a one-bedroom apartment. LaTonya decides to give Daryl Stewart another chance. Daryl got himself a job, pest control for Orkin. Every morning he goes off to work, kisses her goodbye, a man in a uniform. But when she calls his job one day, she learns that Daryl was fired, weeks ago, actually. “But he dresses and goes to work every day,” she says to his boss. Then her phone rings and it’s a drug dealer, telling her that Daryl has traded her car for crack cocaine, and would she like to buy it back? She files a police report, and apart from a brief visit in Las Vegas years later, Jelani has never again seen his father, nor has LaTonya ever received child support. “If I saw my dad on the street,” Jelani says, “I wouldn’t know what he looks like.”

Jelani wakes up slowly. He goes into the bathroom. He’s got to get through his mom’s room to get there. His mom’s boyfriend, Bo, is snoring in her bed; he’ll be snoring for hours. Jelani doesn’t think it’s right that Bo sleeps all day and watches TV. Not that Jelani doesn’t like watching TV, he sure does, but a man gets up and goes to work or school or something. There is a list taped to the wall next to the bathroom sink: “Jelani’s daily bathroom chores. Good morning! 1) Wash face 2) Brush teeth 3) Put deodorant on 4) Pick up clothes off floor 5) Hang wash towel up 6) Make sure water is turned off and lights are out. Thank you son. I love you.” Jelani’s mom believes if you write things down, especially dreams, they come true. She learned that from the Bible, and her list is thumbtacked to the kitchen wall: “1) To own my own daycare business 2) For my business to be successful 3) To own a black shiny new Pontiac Grand Am, with a license plate that reads:

CALIFORNIA PRYR WKS!

4) To own my own home 5) To be the best mom and provider I can be.”

Jelani’s mom is in the kitchen making oatmeal. She is dressed in nice pants and loafers with tassels. Jelani is walking around the house in his long underwear. A couple TVs are on in different rooms, as always, and he is not getting dressed. “Put on your clothes. Now!”

The walls of Jelani’s house are decorated with squares and circles cut from colored construction paper. They are labeled CIRCLE, SQUARE, TRIANGLE. On the stove, a handwritten sign says STOVE, and underneath in red letters is the word HOT! Jelani’s mom is getting ready to run her daycare business out of the house, and he has helped her make the signs. She told him, I’m an entrepreneur. He liked that word, and it felt like a project they were doing together. When she had to learn pediatric CPR, they practiced on each other, and now her certificate is framed on the wall.

As Jelani and his mother head outside, he’s shoving his homework into his backpack. Divine, a pit bull that lives in the backyard next door, throws himself against the chain-link fence that separates the yards. Jelani’s mom wants to be saying, Don’t be teasing that dog, but what’s the use, she’s said it a thousand times. She’s worried that the pit bull will scare the families that she hopes will come to have her babysit their kids.

Oh, shit, she needs Bo to pay the electric, and she’d better remind him because he’ll never remember otherwise. Jelani waits by the gate as LaTonya sticks her head back in the door. Of all the places they’ve lived, this little South Central rental with the palm trees outside is his absolute favorite.

After Jelani’s father disappeared, LaTonya found another apartment, for less rent, and for the next year and a half, she raised Jelani alone. She loved feeding him and washing his clothes. She didn’t have much furniture, just a bed for the both of them, but she kept the place spotless. It felt good to be on her own, but sometimes she got lonely. She got a job with the school district at a daycare in Venice. Sometimes she took Jelani with her, and other days she walked him to a babysitter who lived around the corner.

Bo was dealing crack out of an apartment on Highland when he saw LaTonya walk by holding her son’s hand. She was slim and pretty, wearing a pantsuit. She seemed from another world, a better world. Bo was living the gangster life, and mostly he met girls who wanted drugs for sex—strawberries, he called them. But this girl was different. She didn’t seem to want or need anything. “There goes an angel,” he whistled. “That’s my future.”

And so the next morning, Bo raced outside when he saw her at the mailbox. He was still in his pajamas. He introduced himself and told her she smelled nice. He asked if he could call her. She just laughed. “Don’t you got a girlfriend?” He was out there again the next morning, and every morning for the next week. Sometimes he’d walk beside her a ways. He made her laugh. Finally she gave him her number. Sure, he was probably wild, she knew that from the start, but he was handsome, and, well, he was paying attention to her.

The scar is not the first thing you notice about Bo, but once you get past the bulk of him—he’s six feet and 225 pounds—then you might notice it. It’s a dark, jagged line across his forehead. He got it back in Lorain, Ohio, when he was hit by a car at age three. His head was busted open, his arms and legs broken. He was in a coma, hooked up to life support, and his mother sat at his bedside even when everybody gave up hope. Sometimes he still hears her voice—Why you playing in the streets? You gonna be okay, I’m with you. Junior, I’m gonna whup you when we get home.

Jelani stayed with his grandparents when Bo and LaTonya had their first date. Bo blended her a drink with gin and ice cream and pink lemonade; he put whipped cream on top—pink panties, he called it.

LaTonya never knew what crack looked like until she met Bo. She’d never known a gang member. Before Jelani was born, she’d been a nanny for seven years, starting with an affluent white family in suburban Chino, an hour outside Los Angeles. She’d gotten the job through church. Bo called her square. Her daddy had smoked weed in front of them as children, funny-smelling cigarettes that he would roll in the car as he drove them to school. She didn’t like it then and she didn’t like it now, but nobody had ever paid her this much attention before, and it felt good to have somebody think she was pretty. Soon he was staying overnight.

“Bo was extroverted, and I was Bo’s girl, and nobody could touch Bo’s girl, and I was made up to be some kind of queen,” she says. Daryl had been introverted and sneaky, stealing off for his drugs. Bo was more out with it, and she liked that. He was upfront: This is who I am.

For the first time in his life, Bo felt that, in LaTonya, he really had something special. And for the first time, he felt like he had a lot to lose. But a man’s got to make money. He worked the alley behind their apartment, selling crack. “He had twenty cars in that alley all lined up,” she says. “White folks, every color.” She was always telling him, “You got to put up that money, invest it.” He thought it was going to last forever. He always told her, “I know what I’m doing.”

LaTonya never smoked crack. Bo told her if she ever did it, he’d beat her up. He wanted her pure and clean. Crackheads brought furniture and stereos and jewelry as payment, and these things furnished the apartment. LaTonya had rules: She didn’t allow Bo to deal in the house while Jelani was home. Crack addicts didn’t scare LaTonya; some were middle-aged men who just a few months earlier had families themselves and had held down jobs. Her own father had been a family man until he’d tried crack.

Jelani spent most weekends with his grandparents, and often during the week he’d be with LaTonya’s grandmother, a retired nurse. “I knew it wasn’t good for him to be with me, the way things were going,” LaTonya says. Paw-Paw bought a refurbished computer from Nana’s younger brother, Joseph, who opened a successful computer-training business after the riots with the goal of helping black youth enter the technology age. With Jelani on his lap, Paw-Paw ordered CDs and books online. Paw-Paw introduced him to jazz recordings, the more obscure the better, and for laughs, they’d tune in Dr. Demento. Jelani was the son Cornelius never had and the grandson he’d always hoped for. Most Sundays, Jelani went to church with Nana, who sang in the choir, and LaTonya sometimes came along.

When Jelani wasn’t around, she’d be out in the alley with Bo, but when her son was home, she stayed inside. Bo’s idea of how to play with a child was to crush things between his hands and shout, “This is Bo!” At three, Jelani started preschool at a local daycare. A teacher there said that Jelani was hyperactive and that he should be checked by an expert. So LaTonya took Jelani to UCLA, where he was diagnosed with attention-deficit disorder. The doctor prescribed Ritalin, but when LaTonya researched the drug, she didn’t like what she learned, especially that some kids seem to turn into zombies. She refused to give it to her son. And he seemed to settle down fine.

LaTonya wanted to believe Bo would outgrow selling crack, especially when his gang friends started going to jail. Dre, who brought Bo into the life, got twenty five in Pelican Bay after he was picked up twice for robbery and selling crack. But Bo figured he was smarter than the police. “Don’t be trippin’, baby,” he told her. “Everything’s going to be okay.” At night, he’d count out hundreds of dollars, sometimes thousands. She told him, “You should buy a house with that.” “We got this place, baby, what I need a house for?”

Sometimes the police came around and jacked Bo up against the wall, and sometimes they took him downtown for questioning. LaTonya was with Bo in the alley the first time she saw the police handcuff him. They wanted to talk to him about a murder. “Don’t worry,” he said. “I ain’t trippin’ on this.” Bo promised he’d be home that night, and he was. The police rattled Bo’s cage every now and then, but it wasn’t until 1997 that he was arrested again, and this time it was LaTonya who filed the complaint.

Almost a hundred thousand blacks have left Los Angeles in the past twenty years. A good many have gone to the cemetery, a good many have gone to jail, a good many more have made it to the suburbs, some have made the migration back home to the South. But South Central is LaTonya’s home. This is where she’s staying.

To get to the house where Jelani lives, you exit the Santa Monica Freeway at Vermont Avenue and drive south, passing first the red brick buildings of the University of Southern California and then the new Science Center, built since the riots, and the L.A. Coliseum, before crossing Martin Luther King Boulevard, where national guardsmen were stationed with M16s. A block farther south is where the first person was killed. As you drive, consider that many of the businesses on Vermont for miles south of here were reduced to ashes—a mix of storefront groceries, mom-and-pop shops, and the occasional Korean-owned liquor store. Notice that Payless Shoes and Taco Bell, as promised, have rebuilt, as have a couple banks.

Jelani’s street intersects with Vermont just before the railroad tracks at Slauson Avenue. A pink storefront church is on the corner, and there is a laundry just up the alley, and also a barber college. During the riots, while many businesses were gutted, not a single house was burned. The low-slung wooden bungalows, built in the 1920s, remain the pride of South Central. Should one come on the market, it will fetch upwards of $150,000.

There are palm trees on both sides of Jelani’s street. They are very tall and skinny palm trees. The sky is pale blue overhead, the air very still. Most front lawns are well kept. Most windows have burglar bars. There are no high-rises here, nothing more than a couple stories. Even in the neighborhood known as the Jungle, off Crenshaw Boulevard, four miles west of Jelani’s street, they’ve got lawns.

Jelani and his mother live in a small brown house in the backyard of a larger bungalow owned by Miss Allbirdie Jones. They have been here for two and a half years now—the longest they’ve been in one place since Jelani was born. LaTonya feels lucky to have found the house, and she pays $400 a month for rent. Jelani likes living behind Miss Jones’s house, set back away from the street. He feels safe back here, and if trouble comes through the door, he knows to hide in the closet.

Jelani is looking out the screen door. A few kids have gathered in the driveway next door. “What are they doing, Mom?” he asks.

“Is that your business?”

He shakes his head.

“That’s right,” she says. “It’s not your business.”

LaTonya doesn’t let him play with neighborhood kids, except his cousins when they come to visit his great-grandma, who lives across the street. If LaTonya could keep Jelani inside forever, she would. She only recently began to let him walk the five blocks home from school alone. She used to wait at the school door, until he said, “I want to walk all the way home by myself.” That five blocks is Jelani’s favorite part of the day. He’ll walk home with Brittani and Jahnae, who tease him and tell corny jokes and sometimes hold both his hands. They’re all in the fourth grade. Jelani has a bounce to his walk and big, brown, long-lashed eyes. “Jelani, all you has to do is change that little smartie attitude into a positive attitude,” Brittani tells him. “Like today we were doing history and you made us laugh—that was not a good opportunity.” She’s got braids and long legs in bright pants and a great attitude, and Jelani’s in love with her. She’s not going to marry him because he’s not serious enough.

Fart is Jelani’s favorite word. As in, “Bo likes to fart,” or, “All Bo does is sleep, eat, and fart.” Jelani has a slight Louisiana accent from his grandma’s side of the family, and he elongates the vowel: faaahrt. When he giggles, his shoulders shake. Jelani likes words and has since he was a little boy, when his mom first read him “Curious George.” Some nights, for homework, he must learn a dozen new vocabulary words and use them in a sentence. “I slew my enemies,” he says, balancing on the curb. “I will not indulge in bad behavior.”

Now here’s LaTonya waiting on the corner of their block. She has heard that a ten-year-old kid in the neighborhood is already gangbanging, and she says that drugs are being sold from two houses on the block. The 77th Street Division is the deadliest in California, with eighty two homicides last year, about fifty five of those gang killings. But there is no safe place anywhere, LaTonya says. “I like my neighborhood. I don’t want my son to think he has to move out. To where? Everywhere there are bad apples.”

When Jelani saw the Columbine shootings, he wanted to know if it was real or just TV. Then he wanted to know how the students got guns. LaTonya told him about gun shops and background checks. If he ever saw a gun, he promised, he’d come right home and tell her. She wanted to know how it made him feel to see those kids shooting. “Maybe they needed their moms and dads,” he said. He thought, Yeah, it’s dangerous here, but look at that. He felt sorry for those white kids.

Bo is sleeping as LaTonya and Jelani leave for church. Sometimes LaTonya thinks that Bo is just using their place as a safe house, a retreat from his thug life, and all he seems to do is sleep. He says he’s not living the life anymore, but last night he was washing blood off his hands and face in the shower. And last week, she found a deep bruise on his sternum where somebody had tried to stab him in the heart. She’d long ago stopped asking him to join her in church, or in anything; but it’s Bo she is thinking about as she listens to the soloist. Storms they keep a-raging in my life, goes the song. The congregation is on its feet; the snare drum and the organ are keeping tempo. LaTonya is up, rocking back and forth, and she hears herself shouting out loud with the others, Amen!

The family church is in Watts, a fifteen-minute drive. Jelani’s great-grandmother kept coming here even after she moved to South Central; she is up in the choir today, in African garb and headdress, looking regal. The usher at the door wears white gloves. Outside is Nickerson Gardens, one of the most notorious housing projects in America. It was near here in 1965 that the Watts riots, which killed thirty four, began. To this day, cops are not easily trusted. Last week officers came to serve a warrant and were confronted by a hundred angry residents, some throwing rocks and bottles; extra units were called in to protect the officers from what was described by police as a “near riot.”

Every Sunday, the women in LaTonya’s family drive here for church. LaTonya’s mother also sings in the choir, and once a month, Jelani sings up front with the children’s choir. Today, along with thirty other kids, Jelani is in junior church.

Good morning, junior church!

Jelani wears corduroy pants and a checked shirt. He slouches and twists, all shrugs, like a boxer ducking punches. He is in the front, sitting with his cousin Kiana. The stained-glass window is etched with white orchids. Men in suits move among the children, keeping order. Brother Saunders, a volunteer Sunday-school teacher with a bushy mustache and suspenders, is up front, asking questions.

“How many of you pray?”

Jelani raises a hand.

“How many of you pray every day?”

Jelani doesn’t raise his hand. He pulls at his cousin’s shirt.

“How many of you do things that are wrong?”

Jelani looks around, then puts up his hand.

“God says, ‘If you do things wrong and you come to me, I’ll forgive you.’ ”

Brother Saunders walks over like he might hit Jelani, rears back his open hand.

“If I hit Jelani, what is he supposed to do?”

“Forgive you!” the children shout.

“That means Jelani is not supposed to hit me back, right?”

“Why not?” a kid asks, totally perplexed.

Yeah, why not? thinks Jelani. In karate class, the teacher says, Jelani, your body is your house, your arms are your gates, don’t let anybody in your house. Protect your house! Nothing about forgiveness there. And there was that time last year when the bully was all over him. What was he supposed to do, forgive the kid, who was twice his size? Uh-uh. He got somebody twice the bully’s size. Bo went and had a serious talk with him, and poof, no more bully. Isn’t that the way the world works? And that’s when it’s good to have Bo around, too. That’s when it seemed to Jelani that they were almost a real family. He wasn’t much good for doing stuff or playing ball—Tomorrow, he would always promise Jelani—but having Bo in the house made Jelani feel secure sometimes. Except a couple times, when he was so mad that it seemed like he was going to do violence against LaTonya, and maybe Jelani, too.

“Now, I’m not saying that Jelani should not defend himself!” thunders Brother Saunders. “Jelani, you say, ‘Brother, I will defend myself, and then at an appropriate time, I will forgive you. And I will do both of these things vigorously.’ ”

The real trouble with Bo started in 1997, when Jelani was five. Up until then, Bo had been the man of the house, Jelani’s real father figure, except of course for Paw-Paw Cornelius, who was such a good man and who hovered over LaTonya and Jelani as much as he could without interfering. Cornelius said that of all his grandkids, it was Jelani he worried over most, because of that man Bo.

Bo had always been volatile. When his mother died a few years before, he went back to Ohio alone for the funeral. He broke down at the funeral home and pulled out his gun and waved it around until everybody cleared out, including the preacher. That’s what Bo said happened; LaTonya was never sure. But now he became moody and violent at home. He started lighting his crack pipe in front of LaTonya, and he would dip his cigarettes in a mixture of embalming fluid and PCP that he called sherm. It got to where she felt safer around the crackheads than Bo, and one of Bo’s regular customers even told her, “You need to leave him—he’s going to bring you down.” Things got so bad that LaTonya went to court and had a judge issue a restraining order to keep Bo away.

“Defendant has been physically violent toward me throughout our three-year relationship,” the complaint stated. “He has punched me in the nose, blackened my eyes, slapped and hit me on numerous occasions, and has thrown a chair at me. He also repeatedly makes threats to harm me, my son, and family members.”

The legal voice then gives way to Bo’s voice: “I’ll kill you and your family.”

When LaTonya’s mother read the restraining order for the first time, she was devastated. “Why didn’t you tell me?” she said. When LaTonya was growing up, Pat had been beaten up by her first husband and later by a boyfriend. LaTonya recalls looking “into my mom’s room, and her boyfriend is sitting on top of her, just punching her, and the next day, he’s this nice man in the house who did things for us and bought things for us.”

On the nights when her father was violent, LaTonya would gather her sisters in the other end of the house and read them stories as loud as she could. He had a job at the hospital, and nobody was a more careful dresser or responsible provider. Before her daddy turned to drugs, he was Mr. Clean. A piece of lint outraged him. One night when he was threatening, Pat and the kids fled, and LaTonya still remembers standing in the rain and the dark, waiting for the bus.

After LaTonya got the restraining order, Bo’s luck began to run out. He was arrested five days later for possession of cocaine with the intent to sell. He called her collect from the county jail. “I got stuck and I’ll let you know what happens,” he said. He was sentenced to 270 days in jail. Within weeks of getting out, he was arrested again, this time in Venice with a 69th East Coast Crip named Lil Too Cool, for possession of crack. A few months later, he was busted again for drug possession, and in September 1998 he was sent to prison.

Jelani was six. He didn’t know anything about crack cocaine or jail. All he knew was that Bo was gone and there was no money left to pay the rent.

At around age ten is when it will start for Jelani. What gang you from? is the most dangerous question he can be asked in this neighborhood. The question is coming, and there is no right answer. I don’t bang is the answer mothers tell their sons to say. “Jelani, you say, ‘I don’t bang,’ ” LaTonya says. And hope for the best. I don’t bang got two kids killed just before Christmas. For all his swagger in the world of gangs, Bo cannot protect Jelani; in fact, Bo is a liability. Gang violence is spiking again, and Jelani’s street is Hoover territory, and the Hoover Crips are a large and serious gang known for their ruthlessness. Bo’s a Crip, too, but his set and the Hoovers are sometimes enemies. One neighborhood gangbanger puts it this way: “When little niggers from Hoovers see Bo, if they smoke him, they get more stripes because they got a OG. So Bo in more danger than a little homie.”

The mothers in this neighborhood attribute all this business to the Devil. Devilment is a big word here. The police officers beating Rodney King was the Devil’s work, and the riots were the Devil, too. Damian “Football” Williams hitting Reginald Denny in the head with the cinder block was the Devil. When Williams was arrested thirteen days later, he sobbed and said, “I never seen my daddy. I bet if I had a father, I wouldn’t be in this predicament that I’m in right now.” He told his mother that he was guilty, and she said, “Dame, you know you were wrong, but that was the Devil.”

Gangs are the Devil. Selling crack is the Devil, and smoking it is the Devil, too. It was devilment when Bo hit LaTonya, and it was devilment that one time when he hit Jelani square in the face, and it is devilment to just sit there and not do anything about it.

LaTonya decided to do something about it.

Jelani’s house is in the flight path to LAX, and from his yard he has always loved watching planes come in low over the palm trees. Until September 11 he wanted to be a pilot and would get Paw-Paw and Nana to take him to the airport to watch takeoffs and landings. But after the skies go quiet, Jelani doesn’t want to be a pilot anymore. He wants to be a judge with a gavel, like the black lady judge on TV who sends people to prison. The planes crashing got Jelani thinking about his own life, and this is what he realized: 1) that he, Jelani Stewart, is the man of the house, and 2) the world is made up of good guys and bad guys and very little in between. Jelani wants to judge people and pronounce them bad if they’re bad. After September 11, when LaTonya meets him on the corner after school, Jelani will ask her, “Is he here?” And if Bo is at home, LaTonya will nod her head yes, and Jelani’s face will just fall.

Jelani’s started talking back to Bo. “When you gonna stop making my mama cry?” he says to him. “When you gonna leave us alone?”

“Jelani talks so intelligent,” a fourth-grade mom tells LaTonya at school.

“You think so?” LaTonya laughs.

“He’s always polite and well-mannered,” the mom says. “How’d you do it? Mine talks back to me. He’s ten years old and he’s already sagging his pants, cussing, and looking like a thug.”

“Mine grew up with a thug,” LaTonya says. “So he’s already seen the life and decided he didn’t like it.”

Bo got out of prison two and a half years ago. He had been calling collect and writing, I’m gonna change. I just want my family back. He said he’d go to counseling with LaTonya. He had gotten strong in jail, and Jelani was impressed when he saw him. “Here’s the thing about jail,” he told Jelani. “If you sleep and drink a gang of water, you won’t age much. I’m in the best shape of my life.”

Bo settled back into LaTonya’s little three-room house, and the romance rekindled for a while, and she even had fleeting thoughts that maybe they’d get married. When he was in jail, LaTonya had had fantasies of taking Bo away from his homeboys and the three of them just living a simple life, but where? She even searched the Internet to find an apartment in Lorain, Ohio, where they all could live. But she knew better. And Bo began to stay away at night, and soon he was back in the thug life. The restraining order from years before had done some good, though; if Bo was still a thug, at least he was a mellower thug.

LaTonya will never quite understand what happened next. It may have had something to do with the night two years ago when she was mugged.

It was a Friday night, and LaTonya was wearing her uniform when she got off the bus and began her walk home. She’d been training for a $7.25-an-hour housekeeping job at the Marriott in Manhattan Beach and had cleaned twenty rooms that day. It was her birthday. Her house was just ahead when she heard footsteps behind her; a kid walked past, a sweatshirt hood over his face. His hands were in his pockets, and when he got in front of her, he turned and pulled out a gun. He pointed it at her face, stepped toward her. It all happened so fast. Then he reached out and grabbed her purse. A car pulled up and the kid was gone.

Jelani and Bo were home waiting to celebrate her birthday when LaTonya pounded on the door. “Bo opened it and my mama was crying and she hugged him,” Jelani says. “Bo said, ‘What happened, what happened?’ She could barely breathe. I thought she got shot. I was crying, too. I was crying so hard.”

Bo ran out to the street to see if he could catch the robber or find the purse. LaTonya called the police. “If the police are coming,” Bo said, “I can’t be here. I can’t have nothing to do with the police.”

Bo left, the police came, and Jelani’s stomach got sick that night. “I thought that man was about to come to our house.”

And LaTonya lay awake, holding Jelani, feeling abandoned, thinking, How many times has Bo done that to people—scared them, pulled a gun, maybe killed? And from that night on, LaTonya has said a prayer. She might backslide, and the Devil will try to make her fail, but please, God, deliver me and my son, Jelani, of this man Bo. He’s not meant to be here. I cannot do this alone. I am a sinner, Lord, and I have only myself to blame, but I ask your mercy. Thy will be done.

Finally, this is what happens:

One recent weekend, LaTonya drives into the desert in a rental car with her mother, on their way to Palm Springs to attend a women’s prayer conference. A few thousand African-American women are there, filling an auditorium, hands in the air, some warbling prayers in tongues LaTonya can’t decipher. She is hoping that God will give her a sign.

When Jelani feels fear, he always feels it in his stomach. The day before his mom leaves for the desert, he goes with her to the laundromat on Vermont. He is riding his scooter in the parking lot when he sees the man with the gun. LaTonya is inside, folding laundry. The man is in the alley next to the laundry with his back to Jelani. The man pulls the gun out of his pants and aims; he does this again and again. Jelani gets a good look at the gun and at the man’s hand and the way his hand fits around the gun. Jelani doesn’t want the man to catch him looking, so he takes his scooter inside the laundry and stands next to his mom. He doesn’t want to tell her about the gun, doesn’t want to scare her. All night he has a stomachache.

LaTonya left Bo the key to the house. “Don’t be bringing none of your friends here while I’m gone,” LaTonya said.

“Don’t you worry, nigger.”

“I’m not worried. I’m telling you.”

“Okay.”

“I got spies.”

Jelani is staying at Paw-Paw’s while LaTonya is gone. It’s fun at Paw-Paw’s, like a vacation; Jelani gets to play on the computer, and Paw-Paw always cooks. Paw-Paw is just about the opposite of Bo. He and Nana take Jelani on trips, and Paw-Paw always has a project for Jelani. Today’s project: Build a shed.

Bo walks into the American Barber College on Vermont to get a shave before heading to see his parole officer. He pays his two bucks and sits in an old-fashioned barber chair. The apprentice barber is nineteen years old and just out of jail; his pants are belted low on his hips, and four inches of striped boxers show. FREAK is hand-jagged on his left forearm in wide Old English lettering. “You in a gang?” he asks as Bo sits down. Bo nods. “First Street. East Coast.” The barber is a Crip, too, like Bo, but from another set, the Watergate gang on Crenshaw and Imperial. Bo is wearing a crisp blue shirt with a motocross design and wide blue pants and blue Converse All Stars. When the barber sees Bo wearing Crip colors, with his hair pulled back in a tight ponytail, he sees an OG, an original gangster, a term that signifies a leader, a survivor. The barber tells himself: This nigger’s been doing this shit twenty years longer than me. You’ve got to respect him. Even though he’s not from my hood, he’s still a G.

Out at the desert hotel, LaTonya prays, and others pray for her, a chorus of voices: “Let him go…. You’re strong…. There’s no good for you there….” She catches herself feeling sorry for him but then remembers how she sent him to pay the electric bill last week and he kept half the money.

Paw-Paw and Jelani set to work clearing the back for the new shed. But soon after he starts raking and piling leaves, Jelani begins to wheeze—a deep, gasping, desperate wheeze, like a drowning boy. First, Cornelius just thinks it’s dust, and he sits Jelani in his car with cool air running. “I need my inhaler,” Jelani says. “It’s at my house.” Jelani’s house is locked up, and when Cornelius knocks on the door, Bo isn’t there.

Bo is at the parole office, sitting through a mandatory job-training seminar. The jobs lady up front has a list of places that might employ ex-convicts. “When you go for a job, don’t announce right away that you’re a convict,” she tells them. “Somewhere down the line you’re going to have to tell them. By then maybe they’ll be on your side.”

In Palm Springs, songs of praise are bouncing off the rafters, and the lady evangelist is up front exhorting her sisters to “Rejoice and surrender!” LaTonya is in the middle of the crowd, but she feels alone. So many choices she wishes she’d made different. “I want you all to get up now, sisters,” the evangelist says. “I want you to jog around this hall. Feel God’s energy, His love for you.” LaTonya starts to move.

Taking the bus back from the parole office, Bo stops at the Home Depot. For a moment, he feels inspired. Maybe he’ll get a job. When he first came to Los Angeles, before he started slagging crack, he worked as a security guard, first for Bank of America and then for an art gallery. He worked construction for a while, helped build a Howard Johnson. I’m not afraid to work, he tells himself; but as he walks into the massive Home Depot, with its endless neat aisles of lumber and nails, he feels something like fear. He goes toward the counter, where the manager is standing by a stack of applications, and blurts out, Do you hire convicts?

The manager shakes his head no, resigned, and even as Bo watches the manager, heart racing, he is not sure whether he just said those words or imagined it.

That night when Cornelius checks on Jelani, something’s definitely not right. The boy’s breathing is still labored, and he’s sleeping with his eyes open, which he’s never done before. By dawn, he seems a little improved, but later, as Paw-Paw barbecues outside, Jelani starts wheezing loud enough for a neighbor to suggest that Cornelius take him to the hospital.

LaTonya is up on her feet, like the other women in the auditorium, and yes, she’s jogging, wringing her arms, trying to shake off the old, the depression, the sense of failure. Surrender and rejoice! She can feel the energy in the air. Moving down the aisles, threading past the stage. Suddenly, out of the whole crowd, the lady evangelist reaches out her hand and touches LaTonya’s shoulder, anointing her. She looks into LaTonya’s eyes. “You are going to make a change in your life. Let the walls come down. Trust God.” Out of thousands, it is LaTonya who is anointed. It has happened, the sign she has been waiting for. And she weeps, each new breath filling her with hope.

When LaTonya gets back to her hotel room, an urgent message: It’s about your son. On the phone, LaTonya can hear Jelani’s lungs fighting for breath. Asthma is serious in the neighborhood. Jelani’s friend Jahnae would die from an attack. “We’ve done this before,” she tells her son. “Everything’s going to be okay. Just breathe.”

“Can you come home?”

“Let me speak to Paw-Paw,” she says, and she instructs Cornelius to a nearby hospital where they’ve got Jelani’s records. “Call me as soon as you get back,” she says.

Bo is heading to the corner of Washington and Rimpau, the corner where he became a gangster. He slagged crack here for five years out of the laundry, which everybody called the wash house. It’s a clear day, and he can see the Hollywood sign to the north. He used to stash his rock cocaine in a broken washing machine, and the man working the cash register was on his payroll. All the money went straight into the cash drawer, so when the police came, which they did every other day or so, frisking Bo up against the window, he never had drugs or cash in his pockets. Bo was a natural businessman. Back in Ohio, he had worked as a hospital orderly, and sometimes when old folks in that hospital were getting ready to die, they asked for Bo to sit with them. He had a gift with people that way, the same gift that made him a good drug dealer.

Cornelius and Jelani tear through the streets to the emergency room at Midway Hospital. Jelani is hooked up to machines, blows into a tube to test his lung capacity.

People respect Bo in this neighborhood. This is his turf. Wherever he’s lived, he’s always come back here. It’s his corner. He’s got nothing to sell tonight, and nobody’s got any money, but this is where life happens. Bo climbs into a van. Hey, it’s me, Bo! Damn, Bo. Bo smokes a little Thai stick with the guy in the van, Tupac’s on the radio, they pour something into a cup, drink it. These days he doesn’t hang out here so much. There are other destinations at night, cryptic journeys and transactions, minor hustles. This is the street, this is the life, he tells himself, and I’m a Crip till I die. LaTonya knows it; her mother knows it. I’ll be representing till the casket drops. He takes another hit. I’m a thug, a killer. I’m a gangster. I’ll blast you. I’ll shoot you. I’ll rob you. I’ll kill you. They all know it comes along with the gangster life. They don’t want that in their family! He stomps like an angry bull, and then comes a low wail, like a wound.

LaTonya has a choice to make, whether to leave now and return to Jelani. But she prays and prays on it and decides she must stay in the desert. When God is getting ready to bless you, the evangelist says, the Devil always attacks the person closest to you, trying to take you off your path. Don’t give in.

She can feel the rising voice, all that is ahead, and it scares her. She does not want the confrontation, she does not want to say Go! Jelani sucks the inhaler, a deep breath, a gasp, forcing his lungs open. Paw-Paw holds his hand. Bo lights his crack pipe, sucking the smoke into his lungs. I’m a thug. I’m an OG. And Jesus got angry at those that would desecrate his house! LaTonya knows what’s ahead, and it is terrible. When she returns from the desert, she makes a small sign with a colored marker and tapes it to the front door: CAUTION! GOD IS AT WORK IN THIS HOUSE.

And he says, You’re worthless. He calls her a bitch; that’s the least of it. It’s all f-this and f-that. But Jesus got angry. She calls him a bitch back, just to let him know that she’s not going to back down from the Devil. Then he says, I’m going to smoke you. The wind is howling, her own voice yelling back. He says, I’m going to bust all the windows! She knows he is in despair, angry at himself. He wants her to fight back. She feels the rising heat convulsing her body; letting go is like childbirth itself. I can’t forgive you anymore, I’m not your mama. I have a son.

“You sad, Mama, when I was born?”

“No, I was happy. I was tired and in pain, but I was happy.”

“I thought you didn’t feel anything.”

“I did feel, but not when they was taking you out, ’cause I was asleep.”

“I never know a baby can be in your stomach. I never know that.”

“Yes. Remember on TV when we watched ER, and they were cutting the lady’s stomach to get the baby out?”

“They cut you open with scissors?”

“Knife. They had to cut through six layers to get you out.”

“They cut you open all the way around?”

“Yes, like a smile.”

Jelani doesn’t know what else happened when he was born; she hasn’t told him yet, and nobody seems to talk much about the riots anymore anyway. All he knows is, “I came out of her all wet.” But he does have some questions. “I heard at school that babies come out of your butthole. Is that true?”

The other morning, Jelani made snacks for the four new babies in LaTonya’s care, and then he read them a book. He’s about to start baseball. Paw-Paw will take him to practice. He’s taking Brother Saunders’s etiquette class, which teaches young men how not to behave like thugs. LaTonya now believes that you can’t protect your child from devilment in all its forms, but when you invite the Devil in, you can invite him to leave.

And she packed Bo’s bag and he’s back on his corner. He’s been gone a month now. She hadn’t wanted to tell this story. She’d hidden Bo at first, embarrassed by those years when Jelani was little and she was too comfortable with crack and thugs. But LaTonya decided that telling was testifying, and testifying is a Christian act, and that maybe this is all a part of God answering her prayers. So here it is, the story of the life of her little boy, good and bad. Jelani Stewart is ten years old. On April 30, there will be a big party at a park near LaTonya’s house, with a black clown and a piñata. Everybody he loves will be there. He made the guest list himself.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.