Illustrated by J. Michael Walker

Sept. 5-11, 1997

Unlike the face, with its mixture of trickery and pretence, the behind has a genuine

sincerity that comes quite simply from the fact that we cannot control it.

–Jean-Luc Hennig

I prefer myself a sistah / Red beans and rice didn’t miss her / Baby got back.

–Sir Mix-A-Lot

I have a big butt. Not wide hips, not a preening, weightlifting-enhanced butt thrust up like a chin, not an occasionally saucy rear that throws coquettish glances at strangers when it’s in a good mood and can withdraw like a turtle when it’s not. Every day, my butt wears me—tolerably well, I’d like to think—and has ever since I came full up on puberty about 20 years ago and had to wrestle it back into the Levi 501s it had barely put up with anyway. My butt hollered “I’m mad!” at that point and hasn’t calmed down since. But it is quite my advocate: it introduces me at parties and grants me space among strangers when I am too timorous to ask for it. It will retreat with me only when I am at my gloomiest, and even then it does so reluctantly, a little sullenly, crying out from beneath the most voluminous pants I own “When can we go back?” It has been my greatest trial and the core of my latest, greatest epiphany of self-acceptance, which came only after a day of clothes shopping that yielded the Big Three: pants, skirts, another pair of pants (floating out the mall doors with bags in hand, I thought, Veni, vidi, vici!) I think of my butt as a secret weapon that can be activated without anyone knowing; in the middle of an earnest conversation with a just-met man, I shift in my seat, or if I am standing, lean on one hip as though to momentarily rest the other side. Voila! My points are more salient, my words more muscled and the guy never knew what hit him.

I have come to realize that my butt makes much more than a declaration at parties and small gatherings. Its sheer size makes it politically incorrect in an age in which everything is shrinking: government, computers, distances between people, even car designs. In a new small-world order, it is hopelessly passé. Of course, not fitting—literally and otherwise—has always been a fact of life for black women, who, unfairly or not, are regarded as archetypes of the protuberant butt or at least the spiritual heirs to its African origins. Now, many people will immediately cry that black women have been stereotyped this way, and they’d be right—but I would add that the stereotype is less concerned with body shape than with the sum total of black female sexuality (read: potency), which, while not nearly as problematic as its male counterpart, still makes a whole lot of America uneasy. Thus, an undisguised butt is a reminder of that fact, and I have spent an inordinate number of mornings buried in my closet trying to decide whether or not I should remind other people, and myself, of yet another American irresolution about black folks. On good days I can cut down anxiety with an almost legal argument. (Who defines “big”? How big is “big”?) But more often everything I put on seems to cast a shadow, and then I go back to bed, vexed for falling prey to this most opaque and mean-spirited veil of double consciousness. I am vanquished. Lying under a comforter with my head the only visible orb of my body, I have an éclair.

Women tend to talk freely about butt woes—it is simply another point along the whole food/exercise/diet continuum that dominates too many of our conversations, especially in L.A. But black women do not so readily consign their butts to this sort of pathology, because that is like condemning an integral part of themselves; even talking disparagingly about butts, as if they existed separately from the rest of the body, is pointless and mildly amusing to many. Sounds like this would be the healthiest attitude of all—but it’s not the end of the story, says Gail Elizabeth Wyatt, an African American psychologist at UCLA who recently authored a book about black female sexuality, Stolen Women: Reclaiming Our Sexuality, Taking Back Our Lives. Wyatt is pert and attractive with a brilliant smile and impeccable suits. As you might guess from the title, her book—the first comprehensive study of its kind—is an all-out assault on a host of misperceptions and stereotypes about black women, many of which Wyatt believes are rooted in slavery and attendant notions of sexual servitude. Not to my surprise, one survey she cites found that the black woman/big butt association is among the most enduring of female physical stereotypes; it was the only thing that a majority of the women polled—black, white and other—agreed upon as being characteristic of black women. All right, I ask, but don’t most black women have good-sized butts? Is that, in and of itself, a bad thing? Wyatt says no, explaining that what she objects to is not the butt per se but how it is negatively perceived both by the mainstream and by us. All of us, she says, have effectively reduced the black women to either the “she-devil,” a purely sexual object, or the long-suffering “workhouse” and caretaking “mammy” type, who has no real sexual presence to speak of.

Wyatt insists there is a happy public medium, though she doesn’t claim to have found it yet. Indeed, she herself speaks in the language of extremes: While she doesn’t believe that “we have to give up our sexuality to be heard,” she says neither can we afford to be oblivious about adding fuel to already incendiary notions of the she-devil, more contemporarily known as the skank, ho or skeezer, that hypersexed staple of rap videos. It isn’t fair that black women are held more accountable for the sexual impressions they make, but there it is. To complicate things further, Wyatt says that American culture is increasingly sexualizing its youths. “Unfortunately, the very sexy image has moved from magazine pages to school campuses,” she says. “But when, say, Madonna puts on that image, it’s understood that it’s an image. She can move between being a ho and being a film genius. We don’t move that easily. In other words, black women have little or no context to work with.”

I recognize the truth of black women’s unfortunate history, but I am nonetheless dispirited. If in fact we spend so much time battling myths other people created, if we are always put on the butt defensive, as it were, we’ll never have the psychic space to assess how we really feel about wearing Lycra—and a woman with a sizable butt must have an opinion about it. Another one of Wyatt’s findings is that black women, when it comes to the body parts they like most, tend to focus on hair, nails and feet; everything in between is virtually ignored. “We’re not dealing with our bodies at all,” she says, by way of interpretation. “We’re very conscious of the fact that our image is so bad. We’re not dealing with ourselves individually.”

It’s as if we are still under the microscope under which poor Sarah Baartman found herself in early 19th-century France. More widely known as the “Hottentot Venus,” the African-born Baartman was the empyreal point of a European butt craze in which women wore skirt underpinnings called farthingales and bum-rolls to get the desired effect of an imposing rear and hips. The fantasy was made flesh with the exploration of Africa and the discovery of Baartman and her voluminous butt. Yet though she captured the erotic imagination of the Victorian Age, she was also regarded as a freak, a curiosity; her butt was often depicted in the rotogravures as three times its normal size. She was paraded about and fetishized in public, and her body parts were dissected in private after her death. She was the tortured embodiment of the schism of thought about black women that is ruled by physiology and neatly avoids any discussion of heart and soul.

We all become, as Jean-Luc Hennig points out in his butt-history primer, The Rear View: A Brief and Elegant History of Bottoms Through the Ages, nothing but butts with heads attached. France may have aggrandized the European fascination with the African derrière, but Hennig’s book is disappointingly politic, not to mention incomplete. In the end—pun intended—the book is too stuffy for its own subject, too enamored of its own joke of couching lasciviousness in academia.

The moment of butt reckoning always comes with a mirror—a three-way mirror and you’re pretty much standing at the gates of hell. It is a bad day. I freeze my eyes on a spot in the middle mirror that’s well above my waist with no more gut left to suck in or butt left to pull under. I’m trapped with my own excess, which commands my attention though I will myself not to look. The butt swallows up my peripheral vision and sops up reserve confidence like gravy; it doesn’t merely reject my hopes for a size six, it explodes them with a nearly audible laugh that forces the ill-fated jeans back into an ignominious heap around my ankles. My butt looms triumphant, like Ali dancing over Foreman: Don’t you know who I am? The genes from whence it sprang have suffered too mightily for too many years to be denied a presence, again.

My butt refuses to follow the current trend of black marginalization, nor does it care that we are heading into the millennium with the most collective uncertainty as a people since we first stumbled up out of the dark holds of the slave ships and onto American soil. Oh yes, my butt sees things very clearly; I walk behind it. It dictates all my steps forward and the swagger that informs even the still, muddy sinkholes of depression. It proclaims, from the miserable depths of the sofa where I lie prone, in a stirring Maya Angelou rumble: I rise! I rise! Still I rise! My butt has reserve self-esteem and then some; like the brain, it may even have profound, uncharted capacities to heal.

It also has a social conscience. When I pass a similarly endowed woman in public I relax into a feeling of extended family; I know we are flesh and blood not Frazetta cartoons. Recently I got a very gratifying bit of news from an African friend who called to say she had spotted supermodel Tyra Banks in the Century City Bloomingdale’s. I was mildly curious; what was Tyra like? There was a significant pause. “Erin,” my friend said solemnly, “she has a big butt. ” “Oh,” I said. “You mean, a big butt by model standards.” “No, no. I mean she has a big butt.” “What?” “Yes. Let me tell you.” The finality in her voice had a residue of awe. “A Big Butt.”

It took a few moments for it to sink in. She was one of us. She was a famous model. And she was rumored to be dating Tiger Woods. I could have wept.

Black women are more monolithic than black men are. This is what I realized as I sat through an L.A. Sparks game and thought what an astonishing array of black women there were: young, thin, wide, bony-kneed, sullen-faced, gazelle graceful, hair braided back or flipped up or buzzed clean. This publicly viewed variance is rare. As grievously stereotyped as black men are, they are more publicly visible—as athletes, politicians, ministers, musicians, businessmen—than women are. The black male image is so charged, so undergirded with fear and secret fascination, that black men have sought more vigorously to counter the bad press by raising profiles at every opportunity. Women on the other hand have long been regarded as the backbone of the race, as its uplift, and as such don’t invite nearly as much public scrutiny or engender nearly as much debate. What black women lie between Angela Bassett (she kicks butt, rarely shows it) and the professionally scandalous Lil’ Kim? In that great divide are plenty of women with heart, smarts, guts, supreme style and, certainly not least, butts.

Ange Buckingham is one of those women. She’s an aerobics instructor and personal trainer who wears Lycra, lots of it, though she hardly has the figure one associates with the job. Buckingham is African American, admirably fit but thick in the arms and legs with a butt that curves up and out. “Do you think so? I never thought of it that way,” she says cheerfully. She’s a Detroit native with a head full of twisted braids and a raspy voice that’s likely a product of years spent shouting instructions over dance music. She teaches at the Hollywood YMCA and has created a locally famous alternative to the aerobics regimen called Gospel Aerobics; one newspaper headline described it as “Sweating to the Holies.”

“I don’t look at myself as either big or small,” says Buckingham, who at one point was 200 pounds and still considers herself a work in progress. “I’ve always been athletic. But I’m no Barbie Doll, never have been, and even if I could be that, I wouldn’t want to.” Buckingham’s clients include Toukie Smith, sister of the late fashion designer Willi Smith. Willi, with Toukie as his muse, made clothes cut generously below the waist. Toukie was a longtime paramour of Robert DeNiro and probably the most high-profile (read: Hollywood) purveyor of the big butt. “Now she has that bomb shape—small waist, big butt—but she never talks in terms of, ‘Oh, my butt is big,’” says Buckingham. “It’s more a matter of, ‘I want to tone my arms.‘”

Smith may be the exception; Buckingham admits black women tend to be unhappy with their butts, but it is often less a problem with weight than with self-image and expectations. “They tell me, ‘I don’t like my butt, and I want to lose weight,’” she sighs. “I tell them those are two entirely different things. The proportions of a butt are genetic.” She’s also watched potential clients eye her unfavorably before admitting that Buckingham reflects the physical ideal they had in mind: She was what they wanted to get away from. But Buckingham seems more struck by another memory: going to an African dance class for the first time with a friend and having the instructor encourage students to employ their butts because they were aesthetically important to the dance, to the art form itself. “To hear someone say, ‘No, don’t minimize it, put it out there,’ was startling,” she says. “We were all, out of habit, doing small movements, trying not to stand out. We all looked at each other like, ‘Wow.’ Black women all have this mindset of not going out and shaking it, because we’re taught that’s uncouth or improper or showy. It’s a vicious circle.”

By and large, it’s too bad that black women seem to feel more need to turn down the volume than to turn it up. Between our collective ears, between the mother-earth church lady and the rap-video maven lounging poolside with Big Daddy Kane, is a certain wildness of spirit and imagination, an embrace of life that arcs above both the piety of church and family and the sexual kitsch of gold-painted talons and obvious hair weaves. It’s a spiritualism largely missing from the text-based variety that we know. But when I’m hyperaware of my butt—body satisfaction is the most ephemeral of feelings—it can do no right. It is a sin. That’s when I suffer through a day of what my sister calls the big-butt feeling, the primally strange sensation, like ears inexplicably tingling, of somebody you can’t see watching you.

As has happened in many other instances, black people have taken a white-created pejorative of a black image—a purely external definition of themselves—and not only accepted it but also made it worse. Big butts thus offend a lot of black people as being not just improper but low class and ghettoish, the result of consuming too much fried chicken and fatback. “Look at that!” one black woman will hiss in the direction of another shuffling past, wearing bike shorts with abandon. “Mmm-mm-mmmh. Criminal. Now you know she needs to do something about that.” In the minds of the black upwardly mobile, the butt may connote a dangerous lack of self-analysis (if you don’t check yourself, the song says, you could wreck yourself), a loose, unrestricted appetite for food, sex and dances like the Atomic Dog. It’s like having a big mouth or no table manners. Now we will all accept, even expect, generous butts in a select group of black people—blues and gospel singers, for example, whose emotional excesses can and should be physically manifest—but for most of us who are trying even modestly to Make It, butts are the first thing to bump up against the glass ceiling.

I have a friend who’s been trying to elevate the butt’s social status by publishing a classy pinup calendar called “The Darker Image.” It’s the black answer to the Sports Illustrated version—airbrushed skies, tropical settings—but its models are notably endowed with butts that Kathy Ireland could only dream of, butts that sit up higher than the surf rolling over them and render a thong bikini ridiculously beside the point. Ken said it was hell to get distribution from mainstream bookstores—black by definition is a specialty market, black beauty off the retail radar completely—but he finally got it with Waldenbooks and Barnes & Noble. It’s a small but potentially significant victory for the butt, a commercial admission of its beauty and influence that hasn’t been seen since the days of the Hottentot Venus. I want to give America the big payback: posing next year as Miss January.

Let’s face it: Sexual sophistication is one of those black stereotypes, like dancing prowess, that is not entirely without an upside. It implies a healthy attunement to life, a knowingness. At the same time I was growing acutely butt-conscious at 13 or so, I also started recognizing that implicit power in a figure, how it shaped an attitude and informed a simple walk around the block. In sloping my back and elongating my stride, my butt was literally thrusting me into the world, and I sensed that I had better live up to the costume or it would eventually wear me to death. For me this didn’t mean promiscuity at all but a full blooming of the fact that I stood out, that I made a statement that might begin with my body but that also included budding literary proclivities, powers of observation, silent crushes on boys sitting two rows over. Which is not to say—which is never to say—that my shifting center of gravity wasn’t cause for alarm. I started a lifelong pattern of vacillating between repulsion and satisfaction: My butt branded me, but it also made me more womanly, not to mention more identifiably black. I may have spoken properly and been a shade too light for comfort, but my butt confirmed for all my true ethnic identity.

As one of those physical characteristics of black people that tend to differ measurably from whites’, like hair texture and skin color, the butt demarcates but also, in the context of the history of racial oppression, stands as an object of ridicule. Yet unlike hair and skin, the butt is stubborn, immutable—it can’t be hot-combed or straightened or bleached into submission. It does not assimilate; it never took a slave name. Accentuating a butt is like thumbing a nose at the establishment, like subverting a pinstriped suit with waist-length dreadlocks. And the butt’s blatantly sexual nature makes it seem that much more belligerent in its refusal to go away, to lie down and play dead. About the only thing we can do is cover it up, but even those attempts can inadvertently showcase the butt by imparting a certain intrigue of the unseen. (What is that thing sticking out of the back of her jacket?)

It was tricky, but I absorbed the better aspects of the butt stereotypes, especially the Tootsie Roll walk—the wave, the undulation in spite of itself, the leisurely antithesis of the spring in the step. I liked the walk and how it defied that silly runway gait, with the hips thrust too far forward and the arms dangling back in empty air. That is a pure stand-up apology for butts, a literal bending over backward to admonish the body for any bit of unruliness. Having a butt is more than unruly, it’s immoral—the modern-day equivalent of a woman eating a Ding Dong in public.

And what about Selena, the Tejana superstar? Would she have been as big a phenom if not for her prodigious, cocktail-table behind, without the whispers of possible African origins surrounding it, the mystery? Mexicans complained when Jennifer Lopez was cast as the lead in Selena’s biopic last year, but what else could Hollywood have done? A butt was of prime visual concern, and Lopez’s butt, courtesy of Puerto Rican heritage, was accordingly considered.

What impressed me most was how Selena so neatly countered that butt—which was routinely fitted in Lycra and set off, like dynamite, by cropped tops—with a wholesome sweetness, a kind of wonder at finding herself in such clothes in the first place. She strutted her stuff, though more dutifully than nastily; she was the physical parallel but the actual opposite of young R&B singers like Foxy Brown and Lil’ Kim, who infuse new blood into that most promulgated (but least discussed) black-woman image of the sexually available skeezer.

Grounded in butt size, this image is too potent to be complicated by wholesome sweetness or benign intent. No matter the age or station of the black women who dare to wear revealing dress—Foxy Brown, Aretha, En Vogue, hell, even octogenarian Lena Horne—they’re all variations on a dominant theme of sexiness that is hard-wearing and full but embittered somehow, sexiness with a worldly sneer that dangles a cigarette from its lips and rubs the fatigue from its eyes before it is fully awake. It’s Sister Christian versus the streetwalking, Creole Lady Marmalade. Selena bounded from one end of the stage to the other ruminating on the grand possibilities of love as embodied in her boundless rear; Foxy Brown gyrates her hips and grinds all such possibilities to dust. One seeks knowledge of Eros; the other already numbly knows. To the world at large, the black butt tells the entire story.

I am entirely aware that my butt means different things in different contexts. At a private screening at an art house along the Beverly Hills strip of Wilshire Boulevard, at a gallery opening at the Westside Pavilion, I can wear tight clothes with impunity and no fear of reprisal. If the largely white crowd is looking, it is doing so discreetly, between bites of salmon tart. People may marvel but always at a distance; the most appreciation I might get would be polite applause. But well south or east of there—Inglewood, Crenshaw or Ladera—my butt registers much higher on the social Richter scale. Even the possibility of butt described by a fitted coat or suggested by a hip-length shirt elicits catcalls, compliments, invitations to dinner.

Black men are famous for their audacity with women, even more famous for their predilection for healthy butts. The celebratory butt songs of the last ten years testify: “Da Butt,” “Rump Shaker,” “Baby Got Back,” more brazen versions of such ’70s butt anthems as “Shake Your Groove Thing,” “Shake Your Booty” and of course, the seminal narrative, “The Bertha Butt Boogie.” These songs are plenty affirming, especially the irreverent “Baby Got Back,” in which Sir Mix-A-Lot rightly condemns Cosmo magazine and Jane Fonda for deifying thinness—but they are also vaguely troubling because most of the praises are being sung these days by rappers, many of whom are as quick to denigrate black women as they are to celebrate them; indeed, most artists rarely distinguish between the two. Given recent cultural developments, butt devaluation was perhaps inevitable. As pop music has re-segregated itself, the ruling butt democracy of the dance floor (over which the explicitly inoffensive KC and the Sunshine Band presided), has given way to a butt oligarchy run by self-proclaimed thugz and niggaz 4 life. Call me classist, but my butt deserves a wider audience. So to speak.

But sometimes all that matters is a captive audience, and black men rarely disappoint. Recently, as I was walking in comfortable anonymity through a clean section of Hollywood, I passed by a homeless black man pushing a shopping cart. He took a look at me, stopped his cart in its tracks and shouted in a single breath: “Honey, don’t let the buggy fool you! I got means! How about I take you to lunch? Are you married?” I didn’t take him up, even after he had trailed me for half a block, but I had to admire his nerve; I was in some ways grateful for it. For all the much-discussed black angst about our war between the sexes, approbation from black men is still very much food for my soul, even from the ones with no means. It breaks the lull of assimilation and makes me remember that, for all the dressing-room nightmares I’ve lived and will live, I’d rather be successful at fitting comfortably into my own skin than into clothes meant to cover someone else’s.

The recently departed Gianni Versace was a champion of the bodacious woman: It was he who put Tina Turner in those rump-shaking minis, and a recent Versace memoir in The New Yorker had rapmeisters Spinderella and Salt-N-Pepa provocatively posing in similarly tight, butt-enhancing leather frocks. Yet this kind of self-affirmation veers close to whorishness in the eyes of the public. Tina and many of the young black nouveau riche buy Versace by the truckload; fashion insiders quoted in The New Yorker sniff at Versace designs as being a hair’s breadth away from cheap and vulgar. The designer’s sister and muse, Donatella (his Toukie Smith, as it were), with her shock of platinum hair, nightclub duds and profusion of gold jewelry, is really a Mediterranean Mary J. Blige.

But Versace was an exception; fashion, on the whole, assiduously ignores the butt. Tube dresses, hip-huggers and shrunken T-shirts are touted as body glorifiers, but that claim barely masks their true fuck-everybody-else agenda. It is the season of the leg, the shoulder, the belly, the neck, but the body part that truly makes the clothes is left out—fabric must sweep down and past it, its path uninterrupted by an impudent behind with, God forbid, a life and a fashion statement of its own. Even the more corporeally accepting French have gone on the butt offensive, leading the way in attacking it as a chief “problem area.” In the ads for Christian Dior Svelte Perfect anti-cellulite cream, a naked woman crouches demurely behind a cloud of pink tulle to hide a butt she doesn’t have anyway.

In computer idealizing the butt, we have left the ravishing behind behind. And it can’t catch up; it won’t. It doesn’t want to. Feet were made for dancing, and the butt was made purely for indolence, which has no real place in this age of function and frightening efficiency. Buns of steel? To my butt’s leisurely way of thinking, that ain’t nothing but stale bread.

Some women consider fashion’s disdain of butts the biggest urban conspiracy going. “It’s butt discrimination! Butt segregation!” fumes Jan, whom I’ve known since childhood. Jan is short and compact, well-proportioned. I’ve admired her figure since the sixth grade, when she officially got one. “I mean, I had the first opportunity to buy a $300 pair of Todd Oldham pants on sale for $30,” she says, recalling a recent trip to American Rag on La Brea. “They were my size, six. I went to try them on. Everything was going well from the calves up to the thighs—then the butt screamed, ‘Hell, no!’ These were hip-huggers made for people with no hips. I was pissed. Then I realized that even if I had the $300 to spend, I wouldn’t have been able to spend it. What is that about? Are they telling me I shouldn’t wear high fashion?”

Designer Antthony Mark Hankins complains from the other side: “I’m a healthy black man, and I can’t wear Gauthier,” he laments. Hankins, based in Dallas, found a lucrative niche in designing an eponymous line of clothing with black women in mind. In the tradition of Willi Smith, he cuts roomier without cutting back on style. But for him, black fashion is less about butt considerations than about quality fabrics and Parisian sensibilities—in short, it’s about marketing to women who feel they are too often kept at fashion’s periphery when they want to be in the middle of it. “Black women are about being stylish,” declares Hankins from his headquarters. “I’m so sick of black women being perceived as only wanting to wear loud colors.”

Which isn’t to say that Hankins doesn’t have an appreciation of black women’s particular sartorial inventiveness. “If you look at 1930s photographs, the sisters had it together. They gave clothes their own beat—but they’ve always had to make the look work. We’ve always had to take nothing and make something. Designing for black women keeps me on the cutting edge. We are not doing that one little sweater that pulls it all together. That isn’t what we want.”

Hankins also designs a Sears-distributed line called Sugar Babies, which emphasizes “sex appeal, shows a little bit of silhouette. We love a little bit of cleavage, a little butt.” But the frankly sexy—what Hankins calls “hoochie-mama style”—is not what his customers want; the largest group of black women buying his line are southern, with tastes that tend to the conservative. “That doesn’t mean you hide the butt—it’s there, bam, it’s beautiful—but don’t go showing it with a G-string,” he says with a laugh. Like Gail Wyatt, Hankins has no real maxims about how black women should look, other than that they should fundamentally embrace however they look. “Clothes are our spiritual armor. Self-adornment is so important for African American women. Why should we dim our natural lights? We need to accept who and what we are. If we don’t celebrate our own diversity, we’re right back to the 1950s.”

Hankins is optimistic. “The veil,” he says, “is coming down.”

I was now taking the second-biggest butt challenge (jeans being the first): shopping for a bathing suit. Suits have stretch, sure; they’ll get up over the hips but will throw a butt into horrific relief. I hadn’t shopped for a bikini in a few years. The one rolled up in the comer of my bureau drawer was a cotton, daisy-print, cornflower blue affair I had snatched off a Gap sale rack, ostensibly as an afterthought (“Heaven forbid this girl makes a bathing suit a priority,” I imagined one salesclerk smirking to another after I left the store). But on this day, wandering the sunny, sexually denuded Westside Pavilion with my 12-year-old niece in town and scores of puffy matrons bolstering my courage by the minute, I felt reckless. Dez and I went into a shop called Everything But the Beach. Against the scrubbed white walls hung multiple rows of suits made of neon-bright nylon matte jersey and something that looked like fur. I went straight for the Gilligan’s Island number, a lemon-yellow two-piece printed with giant tropical blossoms. In the dressing room, Dez stood by the mirror like Carol Merrill from Let’s Make A Deal. As casually as possible, I suited up and thought, Here we go. Is it Door Number One, Door Number Two or Door Number Three?

I looked in the mirror and started with surprise. The thing fit. I didn’t look gross. The colors complimented the brown of my skin. I looked round but strong and capable, a somewhat augmented Angela Bassett by the sea. The bottom half was conducive to my butt, which looked at peace. I could get away with exhaling and stooping normally. Dez looked approving. I had another epiphanic flash: My figure is still the soul of the feminine ideal. It has been through the ages. In the ’90s it has merely run afoul in this trend of casting what is good and perfectly logical as something without currency, something that was once a nice idea, but… (cf. affirmative action, civil rights statutes, TVs without remotes).

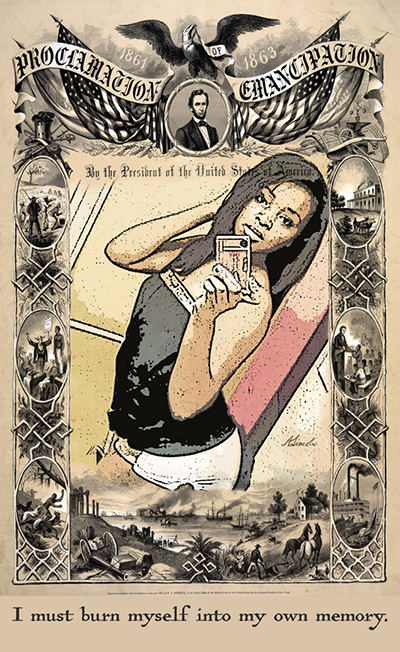

I’ll admit: For all of my hand-wringing, I’m growing accustomed to my butt. It’s a strange and wonderful development of the last six years or so—as I’ve gotten heavier I’ve actually gotten more settled with how I look. Perhaps it’s function of maturity or a realization that fashions aren’t likely to bulk up anytime soon, but I’m much more inclined to reveal myself now, at 35, than I ever was before. I’ve finally concluded that there’s no clever way around my butt, as there never seems to be a clever way around the truth—whatever you try only leads to the most fantastic lies. In the interest of honesty, my butt now gets accent—a lot of stretch, slouch pants, skirts that fall below the navel, platform shoes that punch up my walk. I don’t do big and shapeless anymore, not even in the complete privacy of home. I have finally glimpsed the full, unadulterated length of me and don’t want to obfuscate the image any more than I already do on bad mornings. I must burn myself into my own memory; my butt is more than happy to help.

So what if America, in its infinite wisdom, wants to perpetually help rid me of this bothersome behind with its Self Magazines and L.A. Times “Celebrity Workouts” and the demonizing of complex carbohydrates? More and more, my response has been: I am going to eat cake. I will wear the things that fit—whatever ones I can find—with impunity. I don’t have an issue, I have a groove thing. Kiss my you know what.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.